mHealth video gaming for human papillomavirus vaccination among college men—qualitative inquiry for development

Introduction

Over the past few decades there have been promising progress concerning human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination (1,2). While recent emphasis has primarily focused on vaccinating adolescents prior to sexual activity onset, previous vaccination recommendations varied. There were distinct differences concerning vaccination uptake for men and women and priority groups were also segmented by age. When HPV vaccination recommendations were first adopted in 2009, priority groups identified only included women aged 15 to 26, men up to 21 years, and men ages 22–26 if they identify as a man who has sex with men (MSM) (3). Since then vaccination recommendations have been expanded for all persons through age 26 years old with 2- or 3-dose series dosing depending on age at initial vaccination or condition (4). Therefore, college-age males have been constituted as a catch-up vaccination group (5).

To remedy the low uptake of HPV vaccination among males, several studies have been conducted. They have explored college male knowledge and perceived risk (6), vaccine patterns and perceptions (7), challenges (8) vaccine intentions and behaviors (9) stigma (10) and even racial and ethnic differences (11). Even more recently, research has also been extended towards understanding influencers towards HPV vaccine uptake (12), use of health behavior theory towards intervention development (8,13-16) and the use of some technological advances to improve vaccination rates such as electronic medical record alerts, social media messaging, web-based interventions and mHealth based vaccine reminders (17-19). However, many of the communication technology-based approaches have and continue to focus on females and adolescents (20) indicating a need for more efforts focused on college age men.

Within the public health realm, opportunities to utilize information communication technologies (ICTs) like digital gaming as a behavior change tool are evident. Digital gaming as a public health intervention shows great promise due to the increased gaming behaviors of young adults (women and men). Generally speaking, research indicates that males prefer racing, sports, fighting, survival, action, and collection games whereas females prefer life simulation, dancing, singing, sports, puzzle/strategy and racing games to name a few (21). However, the genre of games played can evolve as age differences emerge (22). Gaming has been used in other public health interventions, focusing on topics such as physical activity/exercise, diabetes prevention and management, smoking prevention, anxiety/depression and broadly sexual health (23-25). While there have been some game-based interventions developed in the area of vaccinations (26). very few games have explored digital gaming specifically for HPV vaccination (27-29). Of the HPV games developed, one focuses on adolescents as a target population group, and the other explores implications of modifying an existing vaccination game to test the effects of avatar customization on HPV vaccine outcomes (29,30). Among the two that were developed and tested in the Unites States, none focused on tailoring video games for college men.

College-age men play video games at significant levels. Not only do they engage in game play but receive feedback through mechanics such as health messages (31). College age men are a population demographic that historically have been gamers. Because of this coupled with game play behaviors, men immerse themselves and take on the attributes of the characters they play. This can impact not only their gaming behaviors but real-world behaviors as well. They see the video game as a form of entertainment and fun, but also as an environment to socially interact with others as well as experience things within the video game that they may never be confident to engage in real life. Video games are a form of education entertainment, influencing health knowledge, attitudes and behaviors while also serving as a form of entertainment. Because they do not detract from the enjoyment of using this health education channel, they are the optimal platform for an HPV intervention or program (32).

There are many benefits of using gaming-based interventions for college age men. According to psychology research, gaming among men promotes cognitive skill development, faster and more accurate attention allocation, enhanced mental rotation abilities, problem solving and neural processing (33). Engaging in game play also encourages intrinsic motivations and therefore real-world motivations and behavior change (34). Therefore, when designing a vaccination-based game specific gaming mechanics should be taken into consideration. Current research identifies role playing, rewards and simulations as common mechanics that contribute to favorable study outcomes. In a recent systematic review, it was identified that in all of the vaccination-based video games studies published between 2013 and 2019, role play and rewards was an evident characteristic among all. Four (n=4) of the seven (n=7) studies indicated that favorable outcomes such as positive attitude and intention to get vaccinated increased and three (n=3) studies reported increased knowledge and literacy (24).

Digital gaming technology as an HPV vaccination programmatic tool can be influential among college age men. Furthermore, we believe that the formative data collected can be guiding tool towards app development for uptake. Therefore, the research questions that guided this exploratory qualitative study included:

- “How should a digital game be designed for male college students on HPV and the HPV vaccine?”

- “How should a digital game be implemented for male college students on HPV and the HPV vaccine?”

- “How should a digital game be evaluated for male college students on HPV and the HPV vaccine?”

We present the following article in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting checklist (available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-29/rc).

Methods

Focus group interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of college-age men at one large research-intensive university in the south. To be included in the study, individuals had to meet the following inclusion criteria: cisgender male, between the ages of 18–26 years old, full time students and non-recipients of the HPV vaccine. Additionally, because previous vaccination recommendations extend for males up until the age of 26 if they have a compromised immune system or identify as MSM, the inclusion criteria were set to obtain data from college males up to the age of 26. Recruitment was conducted via informational study fliers throughout the campus and blasts on departmental email list-serves. All departmental list serve administrators throughout the University were contacted and agreed to distribute study information. The study flier included information relevant to the inclusion criteria, compensation information, days, dates and times focus group sessions would be held, as well as contact information for the Principal Investigator so that they could reserve their spot and confirm participation.

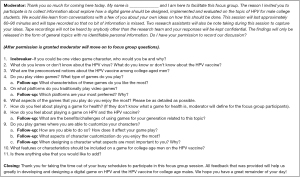

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Approval for this study was granted through the University of Florida Institutional Review Board 2 (No. 2015-U-1488). All students completed an informed consent prior to participating in a focus group session. Focus group participation was voluntary and participants received compensation for participating. Because researchers were more interested in gaming behavior insights, a demographic survey was not used to collect demographic data on focus group participants. Focus groups were conducted by asking open-ended qualitative questions by trained research team members. Questions were developed to college information on how an HPV vaccination digital game should be designed, developed, and evaluated for college-age males. The Focus Group Protocol was developed by the study’s principal investigator and lead author and implemented in all sessions (see Figure 1). The protocol was guided by recommendations and suggestions elicited in conversations with subject matter experts in a previous study (not published). The questions that were asked of focus group participants solicited information on (I) current knowledge of HPV and the HPV vaccine; (II) video game preferences and usage trends; (III) openness/willingness to playing games for health; (IV) video game character customization beliefs and practices; and (V) what features or characteristics should be included in a video game designed for college-age men on HPV.

The interview guide protocol was piloted with a convenience sample of college age men (n=5) prior to the first focus group session to ensure comprehension and clarity of questions and optimal response elicitation. The pilot session was conducted as a focus group session. Participants were able to provide feedback to the interview guide through in-depth interviews. Based upon feedback provided changes were made prior to full implementation of data collection activities. Four focus group sessions were conducted with recruitment goals of six to eight students total participating in each focus group session. A convenience sample of college men were recruited to participate in the focus group sessions. While familiarity with video games were not formally and quantitively assessed, all participants were vocal prior to and during the focus group sessions about their gaming behaviors and experiences. All participants indicated that they were gamers, with great variation in mobile, computer and console gaming. This was confirmed with the depth and variety of information provided during conversation with the sample.

The focus groups were conducted until saturation of ideas was gathered. In total twenty-five participants participated in the focus group sessions which averaged 1.5 to 2 hours in length. Each session was moderated by different team member and to ensure that no ideas were missed, each session was audiotaped for transcription. To ensure consistency among moderators and note-takers, each researcher moderating the focus group sessions was trained and provided with a focus group protocol. During each session, one facilitator moderated the focus group session with one other individual assisting with note-taking. Refreshments were provided, and participants were compensated with a $10 Visa debit card for the feedback provided during the focus group session.

Interview transcripts were transcribed by the research staff. Using the focus group protocol as a guide, a codebook was developed for thematic coding. After transcription, interview transcripts were input and coded using NVivo 10 software to identify emergent themes. To establish inter-rater reliability of emergent codes, three independent researchers independently coded each transcript and meet to discuss the codes identified until 100% agreement was achieved. The codebook assisted in the identification of emergent themes relevant to HPV game development for college-age men. Differences were discussed until a consensus on the coding scheme. Grounded theory was used to develop a codebook for thematic coding and data analysis (35). This coding scheme assisted researchers with identifying emergent frames or themes relevant for HPV game development for college-age men. Results were condensed and organized based upon major themes and subthemes with accompanying quotes provided. Each theme or subtheme was organized in a table format, relative to the research question it addressed (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Research question | Theme | Sub-theme | Notable quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1 | Attractive characteristics and features of the current video games played | Action based excitement or intensity of the game | “Its action based, it’s exciting. Um and the role-playing games, um yeah just that creative freedom and not being tied down to play a game in one specific way. If everyone at this table were to play the same game it would be unlikely that we would all play it the same way. I like that freedom. Usually it’s like an open world sandbox thing where you can just go and draw even when it has no purpose to the game.” (FG1, M1) |

| Online vs. offline | “I can add to that. For like the context again, if I am playing offline solo play, like there are certain settings and you can play god levels, do whatever you want, and maybe you have magic and the magic doesn’t drain when you use your magic, so you have unlimited magic power. But if I’m online everybody is at the same level because if I want to play against you competitively, then I want to beat you purely on skill and have that appearance like I can beat you. That’s the feel for online play so it’s different for me.” (FG2, M6) | ||

| Creative freedom—ability to modify | “It’s a role-playing game and it has like 100s of paths you can take so no one plays the same game at all, even if you play it the same exact way and go for the same missions, you will run into things that are completely different, like you may see a bear one time and none the other.” (FG2, M2) | ||

| Character customization | Doesn’t matter much | I’m pretty indifferent; it doesn’t make that much of a difference. If we were playing a sports tag game, I could be my own character, put more emphasis on being able to dunk. Otherwise, I’m pretty indifferent. (FG3, M4) | |

| Dependent on context playing in | “It really depends on the context on which you are playing in, like because if you are playing offline solo play, my customization doesn’t really matter to me, but if I was playing online like Halo or like first person shooter you know like where you get armor and stuff that shows that I’m a bad ass, I’m going to wear the badass armor but that’s where the customization changes that its shows more of like my prestige.” (FG2, M2) | ||

| Skill based customization (special) | “The customization down to the cheekbone is placed on your face is, if its high or low, and like even, practically everything can be adjusted at some point. Um, I personally don’t, so my roommate is notoriously known for creating the character like he is in real life. And that’s because he wants to be able to see himself on the screen and say look at the dragon I just killed. But for me it’s like you know, I’m going to be the lizard guy because he can breathe underwater and that’s kind of col. I’m now under water wasting time and he’s off killing dragons. Like he’s really placed himself there and for me it’s like let’s take a look at the fantasy experience. Eventually sure, I will like place myself in there, but I don’t know. There are certain people, I don’t know, who are just there to play different things and people like him who want to be immersed.” (FG4, M1) | ||

| RQ1 | Messages to be included | Breaks down HPV into simplest terms | “I think everything you said hot my attention but, you know, if I am not an educated, male – college male – maybe I don’t know what a STD is. So even breaking it down like HPV is a STD.” (FG3, M6) |

| Relevant | “I think the information we present and the game would have to be very accurate and very self – explanatory, you know if I ‘m playing a game and this pop up and I don’t really get it, then therefore this information that I might not gain from it may be a barrier for me getting that knowledge.” (FG4, M3) | ||

| Addition features or characteristics to consider | Short, brief and subtle messages | “People generally don’t want to know about HPV. Ignorant is bliss. I also think that with HPV, create a game where you go around preventing the HPV virus instead of spreading it so you’ll have to change the narrative. Highly commanding objective. College man doesn’t like getting told what to do; it needs to be a subtle message.” (FG2, M2) | |

| Inclusion of characters | “I think it would have to be sort of like low key and hidden behind different things. Like, imagine if it was like the main character had HPV and he has to go back in time to figure out how he got... I mean, this is just a basic example, like if you put different layers on it. So, it’s not just like you’re an HPV like virus cell traveling through the body. But if you put it behind different layers.” (FG1, M6) | ||

| A good storyline or narrative | |||

| Informative | “I think something very informative for people who do not know what HPV is; something very interactive, not just flip pages but a character with the disease and then this happens. Even if I spend 15 minutes, I’m 60 percent more educated.” (FG3, M5) | ||

| Platform used to play video games (consoles) | Benefit—the culture of gaming | “Okay, so maybe like the culture of gaming itself is just built on playing on those consoles and any deviation doesn’t feel like you’re really playing.” (FG1, M4) | |

| Challenge—modifications resulting in banned accounts | “A lot of the stuff, the modifications that be done on the consoles can actually get your account banned. So, you won’t be able to do anything.” (FG4, M1) | ||

| Platform used to play video games (computers) | Benefit—middle ground for all player types | “Yeah, I would say that a computer game would be a good middle ground for console gamers and the mobile app games, but only if it was like a simple game. That way you know, I don’t want to say everyone, but almost everyone, um especially for like the college age group has a laptop or computer that they have access to.” (FG2, M2) |

|

| Challenge—more expensive to play | “It depends, like depending on how data intensive the game is, the biggest barrier would be the price on PCs would be typically more expensive. Not typically, they are more expensive if you want to play at that highest level. You know, a console you’re looking at 3-4—maybe, PC over a 1000.” (FG1, M1) | ||

| RQ1 | Platform used to play video games (smartphone/mobile App) | Benefit—access | “Yeah, I was going to say I think the... major benefit of having a phone game compared to like a computer game or a control game is like everyone has a phone so everyone can play your game is that’s what you’re making it for. But, like what everybody else said like it definitely depends on the type of game that you’re trying to make because it has to translate to that, you know, platform in a way that like makes It fun…” (FG2, M6) |

| Challenge—translation of regular games is still limited | “I think it will get better like really quickly cause they always like just like really push ahead like every year, it’s like two steps ahead in terms of technology. But I think that challenges… umm, phones can’t really handle that much data so it came to like we like playing games that go on forever that like you can unlock a bunch of things and like he said it’s like the freedom types of games like Assassin’s Creed. Like phones would never be able to handle that cause that’ll like use up like more data on your phone.” (FG2, M3) | ||

| RQ2 | Sentiments towards playing a game for health | Wouldn’t seek it outright (not first choice) | “I think it would be more of like a novelty more than anything else like you might be like “oh, like there’s a game about HPV let me check it out but it’s not going to be, like you’re not going to be telling your friends like it’s such a fun game, you should play it.” (FG4, M5) |

| Wouldn’t play in leisure time | “If as a college student I wanted to play something, I would not go for a health-related game, um but at the same time I did virtual school in high school and um when I did, I enjoyed playing the games more than I enjoyed reading the lectures. Um so if it was something that was, you know, if it was something that was a substitute for the lectures then yeah I would do it, but if it’s something that I’m doing in my leisure time, no.” (FG1, M4) | ||

| Integrate or embed HPV messages into games already played | “So, if you put something like the HPV, something that has a real word backing something there, a lot of the people would be like oh yeah, Wow… this is actually something real. That could actually happen. So, I think people would pick up on that a lot and if it was embedded inside a game.” (FG1, M2) | ||

| Game + curriculum | “But would I rather play a health-related game or a health-related lecture, you know on PowerPoint? I would much rather play the health-related game. I think if we are trying to increase knowledge, it’s a more effective way than just lecturing, but yeah sitting and playing a game would be my first choice.” (FG3, M4) | ||

| Packaging of the game is important (message, mode of delivery and marketing) | “I can see this getting, being given out in the health department. Like you said, in the reactive piece. So, if you have this, this app will help you learn more about it.” (FG2, M1) | ||

| “And building off his idea, you know, at health departments or any kind of primary care visit, maybe the type of game would be effective for like practitioners or umm providers to give kids.” (FG1, M2) |

|||

| RQ3 | Knowledge or preconceived notion of the HPV virus | None or very little knowledge | “I think one thing to consider is you asked about preconceived notions and besides it not applying to me, I couldn’t think of any. And I think the biggest thing is ignorance. So, like really working with people from ground zero in terms of this virus.” (FG1, M5) |

| More of an issue in women | “Again, I think it’s just because you hear a lot about how it can disrupt and how bad it is for a female but you don’t really hear about what some of the negative effects of HPV is for males. And actually, I don’t know of any. Not that there aren’t any.” (FG1, M5) | ||

| Not an issue or not on radar | “Yeah similar theme, uh. I don’t know much about it. I actually didn’t even know men could get it until last week so, yeah. It’s never been brought up as an issue to me, um by my doctor, my parents, anyone. Um, yeah, so it’s never really been on my radar.” (FG4, M3) | ||

| Knowledge or preconceived notion of the HPV vaccine | Required for women, not needed or required for men | “I thought that most girls were practically required to get it. Um and I think it was only recommended for guys. If we even talked about, we offered it to guys if they wanted, with all of us not really knowing what was going on. Like why would we go get a shot so.” (FG3, M1) |

|

| Didn’t know it existed for men | “Um I think before hearing your defense, I didn’t really know what there was like oh get a vaccination for HPV. That was like totally new and different for me, like I didn’t even know that was a thing really, yeah.” (FG1, M1) | ||

| If women get the vaccine, then men are covered | “Um, I don’t know, it’s not really in my case, but it’s possible that a preconceived notion that may have is that by women getting the vaccination, it kind of covers them too.” (FG2, M4) | ||

| Impact of character customization | Simulation of real-world experiences | “Visualize the game to play better in real life; I always thought it would be cool like creating an investigative game where you figure out the cure to a disease and that could mimic the real world. Does that make sense? I would say I do play better and would make me play more.” (FG3, M3) | |

| Influences game play and gaming behavior | |||

| Increased self-efficacy | “Um, it depends on what you’re doing. Hopefully, it doesn’t inspire anyone to go out and shooting. If you play a football game, it makes you want to play in real life. More likely to play in real life; increases your belief that you can succeed in the role you’re playing in the real world.” (FG3, M2) | ||

| Increased engagement & interaction | “If there’s an option to customize, then yes. Scanning yourself into the game so that you’re in the game and out there playing. That was pretty cool. Made me want to play the game. It looks like you’re out there playing.” (FG4, M1) |

RQ, research question; STD, sexually transmitted disease; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Results

Game design & development

While there was no demographic data collected on gaming study participants, all focus group participants indicated that they were gamers and engaged in game play on a variety of platform channels. This proved to be beneficial in soliciting feedback and understanding of how to developed a tailored and appropriate game relevant to men. When asked about game design and development, there were several factors that were discussed among the participants. Since a large percentage of the participants identified as gamers, they felt as though a game that was more role playing in nature, and had the same level of action experienced in similar games played would appeal most to college age men. Creative freedom was also emphasized in conversation. Creative freedom for a digital game, can be explored in several ways. This included skill customization and the use of a sandbox (having each player experience something different when playing the game.

“… just that creative freedom and not being tied down to play a game in one specific way. If everyone at this table were to play the same game it would be unlikely that we would all play it the same way. I like that freedom. Usually it’s like an open world sandbox thing where you can just go and draw even when it has no purpose to the game” (FG1, M1).

While avatar customization was brought up, it was emphasized that this type of customization and its effect would be heavily influenced by the type of game itself. While some games commonly played by men, such as Halo and Call of Duty would not be a natural fit, if designed contextually to be an online simulation game, then the use of an avatar may be more appropriate. Additionally, participants felt as though besides being relevant to their population, the game should be informative, include subtle messaging and include a strong storyline. Nearly one third of our participants reported in conversation with focus group facilitators having seen health messages before and during game play; and were open to receiving messages in the future. By incorporating these components, college age men felt as though the game could be more impactful at increasing awareness of the HPV virus and HPV vaccine. This is exemplified below:

“I think something very informative for people who do not know what HPV is; something very interactive, not just flip pages but a character with the disease and then this happens. Even if I spend 15 minutes, I’m 60 percent more educated.” (FG3, M5).

Besides the characteristics, gaming platform was also deemed important. While there were many advantages and disadvantages of each mentioned, ultimately our participants highlighted mobile app-based games as optimal platform due to its increased access and use among the population. They also discussed the ease of play and ease of dissemination but acknowledged that sometimes traditional computer and platform only games do not translate as easily into a mobile format (see Table 1).

Implementation

Besides mobile apps being an optimal channel for game dissemination and uptake, the participants also offered up several ways to actually get college age men to play the HPV vaccine game. While they acknowledged that they would not automatically pick up an HPV game just to play naturally, they offered up many options to consider. This included integrating HPV messaging into already existing popular video games that men already play or creating a game that could be used in conjunction with a health course curriculum. The game could be associated as an assignment and would ensure that the men enrolled would play. A third option also included health care providers/health departments prescribing the game for patients.

“And building off his idea, you know, at health departments or any kind of primary care visit, maybe the type of game would be effective for like practitioners or umm providers to give kids.” (FG1, M2).

Evaluation

Participants gave great insight on how to categorize a digital game as being successful and effective among their peers for HPV vaccine uptake. Because several participants had very to no knowledge about the HPV virus and vaccine, they felt as though measuring knowledge outcomes would be important. In particular, themes such as “Not an issue/not on radar” and “If women get the vaccine then men are covered” emerged. Conversations further highlighted the issue of the HPV vaccine being framed as a woman’s issue impacting the general awareness among men. This is exemplified in the quotes below:

“That it’s not as pertinent to men as it is to women. Being framed as a sexual promiscuous lifestyle. Because it is more frequently covered as causative to cervical cancer, it’s not as noticed.” (FG2, M5).

“… Several different like strains of the HPV and that the vaccination doesn’t cover all of them but I think it covers like the most prominent ones or the most prevalent ones I guess. Um but same thing, as he said, you know I knew that it could cause cervical cancer, and like I said before it just really wasn’t on my radar because I don’t have a cervix.” (FG3, M4).

In a digital game, besides knowledge it was important to assess other aspects of impact. These included (I) increased self-efficacy of the player (increased confidence of the player during game play to prevent spread of HPV and receive the vaccine in the game); (II) increased engagement and interaction with the game itself; and (III) game to real world behavior change (i.e., HPV vaccine initiation and completion with a healthcare provider or health agency). Participants thought the only way to increase the impact would be through the use of simulated real-world experiences, especially for a game centered on HPV (see Table 1).

Conclusions

There was a great wealth of data collected from this qualitative study, as focus group participants provided insight concerning game mechanics, design and implementation. They suggested rather than developing an HPV-specific game, that researchers should consider embedding messages into popular games already played or developing a game to be used as part of a course curriculum. Although there were many benefits and challenges associated with each platform type, college-age men in our study indicated that they preferred towards the use of a mobile app or some type of downloadable technology for an HPV game. Computer games were seen as a middle ground platform (easy to pick up and play for all types of gamers) however, the extensive opportunities that existed for the downloadable technology emerged to be the key advantage for use among college-age men. With the continual advances in technology and particularly mobile phones, a gaming intervention can be tailored to the specific preferences of the user; and emphasized that the ability to tailor in-game experiences or experience different things each time they played (creative freedom) was also important. This tailoring can personalize the experience for the users while addressing cultural factors that can be influential on sexual health outcomes (36).

Based on a consumer research theory premise called the “extension of the self” (37) many college students also view the mobile phone as an extension of themselves due to their increased utilization of the object and their perceived control and power over it. Because the possession of a mobile phone can assist in the reflection of one’s identity a mobile game can have immense saliency and effect on HPV vaccine uptake among college-age men. Focus group participants also highlighted that the game should be role-playing in nature to capture the attention of the targeted audience. According to Prensky (38), when intending to change or alter behaviors, digital games should be role-playing in nature and integrate learning activities that incorporate imitation, feedback, coaching, and practice. A mobile based HPV game or HPV messages imbedded in games played can have immense benefits for encouraging not only vaccination behaviors among men, but other behaviors relative to their overall health. This is increasingly promising as research literature has highlighted that men use less preventative health care services and generally do not seek treatment when experiencing health issues (39). These negative behaviors, are even more extended to those who identify with the sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ+) population group (40).

Although mobile app or mobile technology games were seen as most favorable among players, many of our focus group participants were not convinced that college age men would intentional play a game centered about the HPV. Participants communicated that there should be some incentive or motivation attached to encourage initial engagement and interaction.

Primary care providers are cited as one of the most influential factors impacting vaccine imitation and completion among adolescent and young adult populations (41). However, there can be many disparities with the implementation of practice standards including the strength and quality of the provider recommendation, where it is emphasized as a cancer prevention strategy or linked to sexual health, the use of reminder systems or technology, the nurse/clinical staff interaction, same day vaccine initiation practices and educational tools used to supplement provider recommendation (42,43). When patients go to healthcare providers to seek care, they are often provided a variety of patient education tools which can include brochures and handouts, fact sheets, videos, posters, infographics and websites (44,45). This may not resonate with younger populations, therefore increasing the opportunity for the provider to “prescribe” the video gaming so that they can learn more after leaving or as they are waiting to be seen by a healthcare provider. The prescription of mHealth HPV game by healthcare providers could provide dual opportunities for motivation for game play and improving health system improvement, specifically related to HPV vaccination. This innovative strategy also has additional benefits. Not only does it decrease the uncomfortableness and uncertainty of healthcare providers addressing or communicating with males about HPV but it also allows for males to seek further health information in a gaming format privately about something that can be seen as a stigmatizing topic. Overall this strategy will increase current missed opportunities for knowledge gain/education increase by the target population relative to an important issue. As gaming literature supports, “Opportunities exist through simulation and Internet-based training modules to advance clinical competence in knowledge acquisition, patient education, and processes, such as prescription guideline adherence to address the opioid crisis and other urgent health concerns” (46). By optimizing the patient educational experience as a “play as you wait” option, it would encourage game play of the mobile HPV game since participants in our study identified that young men may not naturally pick up and play an HPV vaccination game outright.

A digital health game designed for HPV vaccination uptake among college age men should match in the game mechanics similar to off the shelf games already played by college age men. There should be a balance of content and design. In addition to the excitement, graphics and technological appeal, an HPV digital game should focus on HPV knowledge gains, and address the pre-conceived notions surrounding the HPV vaccine and virus. Messages of the game should be brief and highly relevant but subtle enough to be informative. Additionally, the HPV game should include characters involved in some type of storyline or narrative and allow for interaction. Overall, consensus gathered communicates that the mobile-based digital game can be influential as an education and communication tool for reaching college age men.

Based upon the feedback gathered for our study participants, combined with preliminary data collected in an experimental study implemented and evaluated on the feasibility of customization on HPV outcomes (30), next steps for game development include (I) the creation of game design including gaming mechanics, narratives and decision tree; (II) game prototype development; (III) feasibility/beta testing; (IV) revisions; (V) patent and copyright protections; and (VI) pilot testing to determine impact among priority population prior to market release. While game design can be an iterative and lengthy process, our team is confident that utilizing a mobile-based approach to game design is the optimum strategy towards increasing HPV vaccine initiation and completion rates among young men.

Acknowledgments

The results discussed in this study are part of a larger dissertation study conducted at the University of Florida. While the results have not been published elsewhere, the entire dissertation study has been made available online via the Library Services at the University of Florida.

Funding: This work was supported by UF STEM Translational Communication Research Program (UL1 TR000064) NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Grant.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist. Available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-29/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-29/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-29/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Approval for this study was granted through the University of Florida Institutional Review Board 2 (No. 2015-U-1488). All students completed an informed consent prior to participating in a focus group session.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Jones C. The Past, Present, and Future of HPV: Can Vaccination Help Eliminate Cervical Cancer. 2021 Sept 28; Retrieved January 1st, 2022. Available online: https://www.aacr.org/blog/2021/09/28/the-past-present-and-future-of-hpv-can-vaccination-help-eliminate-cervical-cancer/

- Drolet M, Bénard É, Pérez N, et al. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019;394:497-509. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brandt HM, Sundstrom B, Monroe CM, et al. Evaluating a Technology-Mediated HPV Vaccination Awareness Intervention: A Controlled, Quasi-Experimental, Mixed Methods Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8:749. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. HPV Vaccination Recommendations. 2021 Nov 16; Retrieved November 3oth, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:698-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz ML, Krieger JL, Roberto AJ. Human papillomavirus (HPV): college male's knowledge, perceived risk, sources of information, vaccine barriers and communication. J Mens Health 2011;8:175-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fontenot HB, Fantasia HC, Charyk A, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) risk factors, vaccination patterns, and vaccine perceptions among a sample of male college students. J Am Coll Health 2014;62:186-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL. HPV vaccine and males: issues and challenges. Gynecol Oncol 2010;117:S26-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HY, Lust K, Vang S, et al. Male Undergraduates' HPV Vaccination Behavior: Implications for Achieving HPV-Associated Cancer Equity. J Community Health 2018;43:459-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones G, Perez S, Huta V, et al. The role of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related stigma on HPV vaccine decision-making among college males. J Am Coll Health 2016;64:545-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper DL, Zellner-Lawrence T, Mubasher M, et al. Examining HPV Awareness, Sexual Behavior, and Intent to Receive the HPV Vaccine Among Racial/Ethnic Male College Students 18-27 years. Am J Mens Health 2018;12:1966-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LaJoie AS, Kerr JC, Clover RD, et al. Influencers and preference predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among US male and female young adult college students. Papillomavirus Res 2018;5:114-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCutcheon T, Schaar G, Parker KL. Pender's Health Promotion Model and HPV Health-Promoting Behaviors among College-Aged Males: Concept Integration. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing 2016;10:12-19.

- Grace-Leitch L, Shneyderman Y. Using the Health Belief Model to Examine the Link between HPV Knowledge and Self-Efficacy for Preventive Behaviors of Male Students at a Two-Year College in New York City. Behav Med 2016;42:205-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catalano HP, Knowlden AP, Birch DA, et al. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to predict HPV vaccination intentions of college men. J Am Coll Health 2017;65:197-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnard M, George P, Perryman ML, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and uptake in college students: Implications from the Precaution Adoption Process Model. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182266. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin S, Warner EL, Kirchhoff AC, et al. An Electronic Medical Record Alert Intervention to Improve HPV Vaccination Among Eligible Male College Students at a University Student Health Center. J Community Health 2018;43:756-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hughes CT, Kirtz S, Ramondetta LM, et al. Designing and implementing an educational social media campaign to increase HPV vaccine awareness among men on a large college campus. Am J Health Educ. 2020;51:87-97. [Crossref]

- Reiter PL, Katz ML, Bauermeister JA, et al. Increasing Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among Young Gay and Bisexual Men: A Randomized Pilot Trial of the Outsmart HPV Intervention. LGBT Health 2018;5:325-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Francis DB, Cates JR, Wagner KPG, et al. Communication technologies to improve HPV vaccination initiation and completion: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:1280-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarz AF, Huertas-Delgado FJ, Cardon G, et al. Design Features Associated with User Engagement in Digital Games for Healthy Lifestyle Promotion in Youth: A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Studies. Games Health J 2020;9:150-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown A. Younger men play video games, but so do a diverse group of other Americans. Retrieved June 30th, 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/11/younger-men-play-video-games-but-so-do-a-diverse-group-of-other-americans/

- Wattanasoontorn V, Boada I, García R, et al. Serious games for health. Entertainment Computing 2013;4:231-47. [Crossref]

- DeSmet A, Shegog R, Van Ryckeghem D, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Interventions for Sexual Health Promotion Involving Serious Digital Games. Games Health J 2015;4:78-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim J, Song H, Merrill K Jr, et al. Using Serious Games for Antismoking Health Campaigns: Experimental Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020;8:e18528. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montagni I, Mabchour I, Tzourio C. Digital Gamification to Enhance Vaccine Knowledge and Uptake: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2020;8:e16983. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amresh A, Chia-Chen A, Baron CT. A Game Based Intervention to Promote HPV Vaccination among Adolescents. In: 2019 IEEE 7th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH). Kyoto, Japan: IEEE; 2019 Aug 5:1-6.

- Chen AC, Todd M, Amresh A, et al. A pilot study of computerized, tailored intervention to promote HPV vaccination in Mexican-heritage adolescents. GSTF Journal of Nursing and Health Care 2017;5: [Crossref]

- Cates JR, Fuemmeler BF, Diehl SJ, et al. Developing a Serious Videogame for Preteens to Motivate HPV Vaccination Decision Making: Land of Secret Gardens. Games Health J 2018;7:51-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Darville G, Anderson-Lewis C, Stellefson M, et al. Customization of avatars in a HPV digital gaming intervention for college-age males: An experimental study. Simul Gaming 2018;49:515-37. [Crossref]

- Baranowski T, Buday R, Thompson DI, et al. Playing for real: video games and stories for health-related behavior change. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:74-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baranowski T, Blumberg F, Buday R, et al. Games for Health for Children-Current Status and Needed Research. Games Health J 2016;5:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Granic I, Lobel A, Engels RC. The benefits of playing video games. Am Psychol 2014;69:66-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hwang J, Lu AS. Narrative and active video game in separate and additive effects of physical activity and cognitive function among young adults. Sci Rep 2018;8:11020. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems 1965;12:436-45. [Crossref]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Lee JJ, Kantor LM, et al. Potential for using online and mobile education with parents and adolescents to impact sexual and reproductive health. Prev Sci 2015;16:53-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belk RW. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 1988;15:139-68. [Crossref]

- Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon 2001;9:1-6.

- Novak JR, Peak T, Gast J, et al. Associations Between Masculine Norms and Health-Care Utilization in Highly Religious, Heterosexual Men. Am J Mens Health 2019;13:1557988319856739. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonvicini KA. LGBT healthcare disparities: What progress have we made? Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:2357-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shay LA, Baldwin AS, Betts AC, et al. Parent-Provider Communication of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dilley SE, Peral S, Straughn JM Jr, et al. The challenge of HPV vaccination uptake and opportunities for solutions: Lessons learned from Alabama. Prev Med 2018;113:124-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohammed KA, Geneus CJ, Osazuwa-Peters N, et al. Disparities in Provider Recommendation of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for U.S. Adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:592-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patient Education at a Glance. 2019 May 7; Retrieved Dec 5th, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/patient-ed.html#ed

- MedlinePlus. Choosing effective patient education materials. 2022 Jan 12; Retrieved Jan 20th, 2022. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000455.htm

- White EJ, Lewis JH, McCoy L. Gaming science innovations to integrate health systems science into medical education and practice. Adv Med Educ Pract 2018;9:407-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Darville-Sanders G, Anderson-Lewis C, Stellefson M, Lee YH, MacInnes J, Pigg RM, Mercado R, Gaddis C. mHealth video gaming for human papillomavirus vaccination among college men—qualitative inquiry for development. mHealth 2022;8:22.