Pregnancy posting: exploring characteristics of social media posts around pregnancy and user engagement

Introduction

Pregnancy can be a period marked with intense information seeking and decision making behaviors. Historically, such information was obtained via healthcare providers, books, and family and peer networks (1,2). With the expansion of technology and smartphone applications as well as a dissatisfaction with the prenatal care appointment structure (3), many pregnant women are turning to online sources for information (3). Pregnant women use the Internet for a variety of pregnancy-related reasons, ranging from information seeking to decision-making and sharing of experiences (4,5). Many women report using smartphone applications (i.e., apps) for pregnancy-related purposes (5,6) and increasingly the app market is focusing on pregnancy. In their content analysis of pregnancy-related apps, Tripp et al. (7) found that 40% of applications had information searching features while 19% had medical tools for tracking.

Research finds that women are utilizing digital devices and online platforms for health information through formal and informal channels including specially designed apps, medical websites, and Facebook groups (8-10). As such, interventions for healthy pregnancy utilize these digital resources and have shown positive influences on health-related outcomes (10). For instance, web-based interventions have helped reduce gestational weight gain (11), increase activity levels (8), and lower perinatal/postnatal depressive symptoms (12-14). Additionally, texting interventions have shown improvement in maternal and child health outcomes (15) such as less gestational weight gain (11). However, far less research has been focused on interventions through existing and highly popular social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram. Further, as these are largely image sharing platforms, research has yet to explore the characteristics of posts that capture women’s attention, are liked by pregnant women, and generate more comments, sharing, and/or discussion. If interventions want to leverage these existing and highly popular platforms (16), understanding the aspects that are enjoyable to women is essential. Therefore, this study explores the characteristics of posts on four popular Instagram pregnancy channels and four Facebook pregnancy group pages over a 7-day period.

Mobile device supports for pregnancy

Mobile health, i.e., mHealth, research has explored web-based, text-based, and social media-focused interventions for improving health attitudes and behaviors as well as health literacy. Since people use these platforms for health-related needs, leveraging them for intervention makes sense. For instance, Oh and colleagues (17) found that almost 40% of their 291 participants pursued social support for a health issue on a social media platform and such use improved health self-efficacy as well as perceived emotional support. Although web-based and text-based interventions have a promising future in health promotion, some argue that today’s technology users can become overwhelmed by the sheer number of smartphone apps on the market, making them less effective (18). In the area of apps focused on pregnancy, they can vary greatly in the content they provide (19), increasing the need for numerous apps to meet different pregnancy-related needs. Since social media have already been shown to be an effective tool to communicate health information (20), and include platforms that women typically utilize on a regular basis (21), capitalizing on existing types of use may be a more suitable mechanism to improve prenatal and postnatal knowledge and health.

In order to leverage existing social media platforms to support pregnant and postnatal women’s health, posts would need to be presented in a way that is appealing to users, captures attention when posted in a (potential) sea of other posts, and in a form and tone to which users are receptive. Understanding more about the current landscape of pregnancy-related social media can help inform the use of these platforms as a vehicle for health information and potentially behavior change without the added burden of another application, text notifications, or active web-searching. Knowing more about what information women are attending to and sharing online can provide information to health professional on how best, and through which avenues, to provide prenatal and postnatal information. Therefore, this study examines the characteristics of Facebook and Instagram posts related to pregnancy and postpartum periods and systematically captures how people are engaging with these posts in order to provide insights into how best to provide pregnancy-related information via social media platforms.

Methods

This study addresses two research questions: (I) what are the general characteristics of the pregnancy-related posts available to users of two major social media platforms, Instagram and Facebook, and more specifically; (II) what are the characteristics of the posts that have the highest and lowest amount of attention from users. To answer these questions, an in-depth content analysis of these two highly used social media platforms was conducted. Capturing all posts in a 7-day period from 4 Facebook groups and 4 Instagram channels, we coded the nature, content, and purpose of each post as well as the number of likes, shares, and comments for each. The social media groups were What to Expect (both platforms; Facebook and Instagram), The bump (both), Baby Center (both), Essential baby on Facebook, and Scarymommy on Instagram. These groups were selected because they have public pages, are focused on numerous aspects of pregnancy, and have a large number of followers (182,000 to 2,527,712 followers). As these groups deal with parenting in general, only posts that were pregnancy-related or related to children under 2 years of age were included. Posts about fertility-related conceiving or miscarriage were excluded. Posts within a 7-day timeframe (7 pm on 1/27/19 to 7 pm on 2/3/19), meeting eligibility requirements were screen captured and compiled for coding.

Coding

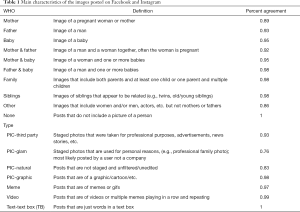

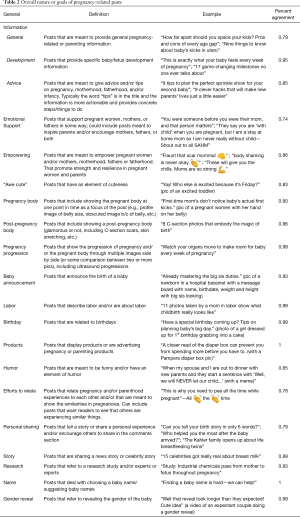

The initial round of coding used descriptive coding (22) where each post was assigned codes that described the general nature of the post. A post was defined as the picture and text (including caption, hashtags/#, and tags/@) initially posted together). A list of pre-determined codes was initially used and further modified as coding continued. Given the nature of social media posts, some predetermined codes included the type of picture (e.g., glamour (make-up, professional or edits/enhanced), natural, text/written words only and pregnancy-related themes (e.g., pregnancy progression, pregnancy body, and post-pregnancy body). The resulting codebook consisted of 45 major codes including sub-codes underneath more general codes (e.g., information: general, developmental, or advice). For example, one post was coded as a natural picture of a mother and baby with the perceived intent to provide emotional support (see Figure 1 for an example post). A full description of codes can be found in Tables 1 and 2. Inter-rater reliability was done by randomly selecting 10 posts from each site (40 from Facebook and 40 from Instagram) to be double coded. Percent agreements were averaged across code and coders. In general, percent agreement was good across categories (mean r=0.92; range 0.76–1.0, see Tables 1 and 2).

Full table

Full table

In addition to coding the characteristics of each post, details were recorded for the number of likes, comments, and Facebook sharing (although sharing is possible on Instagram the platform does not display the frequency of sharing on the post). Additionally, since sites have different numbers of followers, we calculated the percent of the site’s network that liked, commented, or shared each post.

Given the descriptive nature of this study, univariate statistics of the posts for the two platforms and eight sites were calculated. Additional comparisons were made across platforms in terms of the most commonly used qualitative codes, posts that were duplicated on both platforms, and characteristics of most popular and least popular posts. The popularity of posts was determined by comparing posts that were at least two standard deviations above the mean for the proportion of network that liked, commented, or shared the post. All proportions were standardized and popular posts had z-scores above 2, while unpopular posts had z-scores of −2 or lower. Finally, logistic regression analyses were performed to determine what post characteristics predicted being popular or unpopular on Facebook, Instagram, or across both platforms. As a few of the same posts appeared on both Facebook and Instagram, comparisons of their popularity were also made to assess if characteristics of being liked vary by platform type.

Results

Characteristics of Facebook and Instagram posts

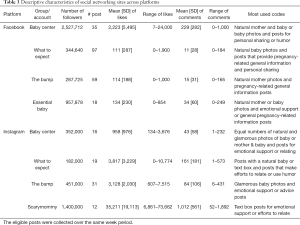

Across Facebook and Instagram platforms, the amount of eligible posts in a 7-day period varied greatly from 18 to 100 posts for Facebook and 12 to 32 posts for Instagram. In total, 288 posts were coded. Table 3 shows the general characteristics of each site by platform including number of followers, number of posts, statistics for likes and comments, and most commonly used qualitative codes. The pictures posted on Facebook tended to be natural (selfies, little to no makeup or apparent photo editing) pictures of mothers or baby while Instagram posts tended to involve more glamorized images of mother or mother and baby (e.g., professional level images, use of makeup, clear photo-editing) or simple textboxes without a person in frame. Facebook posts tended to be related to general information about pregnancy and personal sharing of information while Instagram had more posts with emotional support themes or attempts at making pregnancy relatable. For further descriptive characteristics by platforms please see Table 3.

Full table

Popularity of types of posts

Our target pages/channels had large networks of followers (182,000 to 2,527,712 followers; mean =812,869, SD =805,587) and commenting and liking of posts were done by only a small proportion of these networks (comments: mean =0.02%, SD =0.04%; likes: mean =0.36%, SD =0.89%). The distributions of percentage of comments and likes for the week of posts per site were heavily skewed to the right, indicating very few posts garnered high numbers of comments or likes relative to the total followers of the site.

Posts with the most likes (two standard deviations above the mean for that site) were most likely to attempt to make pregnancy more relatable (e.g., “It’s totally natural when you have a toddler…Right?”), offer emotional support to parents (e.g., a text box saying ‘you were someone before you were their mom, and that person matters’ with associated text “Find her and take care of her”) and/or have some humorous elements (e.g., a text box “Can’t believe I shared my body with a child that won’t even share their M&Ms with me”) (mean =0.50, 0.56, and 0.31 respectively). This was evidenced for both Facebook and Instagram posts. In terms of posts eliciting the most comments, posts encouraging people to share or add to the dialog (e.g., “What baby milestone are you most looking forward to?”), posts that try to make pregnancy relatable, and/or were humorous had the highest percentage of comments (mean =0.31, 0.62, and 0.38 respectively). The types of posts most often shared were posts that had humorous and/or emotional supportive elements. For examples of posts at the top end of the distribution, please refer to Figure 1. Finally, the odds of a post being popular were greater for posts using textboxes (OR =21.06, P<0.001) as well as posts that attempted to make pregnancy more relatable (OR =4.21, P<0.01; e.g., “This is why you need to pee all the time while pregnant—All  the

the  time”) and posts that offered emotional support (OR =4.62, P<0.01; e.g., textbox “Which stage of motherhood is the hardest? Probably the one you’re in right now. This too shall pass, Mama.”).

time”) and posts that offered emotional support (OR =4.62, P<0.01; e.g., textbox “Which stage of motherhood is the hardest? Probably the one you’re in right now. This too shall pass, Mama.”).

Determining unpopular posts was more difficult given the skewed nature of the distributions. In general, most posts had few likes, comments, or shares per total number of followers. Thus, no posts had a z-score of −2. Additionally, commenting patterns across Facebook and Instagram differed greatly. Thus, we defined unpopular posts on Facebook as those with a total sum of equal to or less than 10 across the like and comment categories (e.g., 0 comments & 9 likes or 1 comment & 0 likes). Instagram posts had very few zeroes indicating that most posts had some amount of commenting or liking. Not commenting on, liking, or sharing was more common on Facebook. Unpopular posts on Instagram were defined by posts with less than or equal to 0.005% of comments per followers or 0.10% for likes per followers, as likes were more common on Instagram compared to comments.

On Facebook ‘What to Expect’ had 36 posts, ‘the bump’ had 13 posts, ‘baby center’ had 1 post, and ‘essential baby’ had 4 post that met the unpopular requirements. A majority of these posts were coded with general pregnancy-related information. As for unpopular posts on Instagram, ‘What to Expect’ had 7 posts, ‘the bump’ had 9 posts, ‘baby center’ had 10 post, and ‘scarymommy’ had 1 post. Most of these posts featured an ‘Awe-Cute’ characteristic, which are images that are meant to be adorable such as a baby dressed up like a French fry in a carton of French fries (refer to Figures 1 & 2 for examples). Finally, the odds of a post being unpopular on Facebook were greater for posts with more commercialized photos for third party purposes (e.g., selling a baby product) (OR =2.32, P<0.05) and posts that provided general pregnancy information (OR =2.17, P<0.05; e.g., “8 things I wish someone had told me about the first 24 hours with a newborn”). Unpopular posts on Instagram were more likely to have a picture of a baby (OR =4.81, P<0.01) or “awe-cute” posts (OR =6.29, P<0.001).

Comparisons across duplicated posts on both Facebook and Instagram

The pregnancy-related site ‘What to Expect’ had the most posts that were on both Facebook and Instagram. Across the 16 duplicated posts, all but two posts had more user engagement on Instagram as evidenced by more likes and comments per total number of followers compared to Facebook. For example, the same post on both platforms received 548 likes (0.16%) and 165 comments (0.05%) on Facebook to compared to 7,678 likes (4.22%) and 485 comments (0.27%) on Instagram. ‘The bump’ page on both Facebook and Instagram had three duplicated posts and all posts had more user engagement on Instagram compared to Facebook. Characteristics of posts that were duplicated on both platforms involved humor or posts that made an effort to make pregnancy more relatable as well as adorable pictures (i.e., ‘awe-cute’) and personal sharing posts (e.g., “Yuuuup. What did you over-purchase with baby no. 1?”).

Discussion

Facebook and Instagram are highly popular platforms (21) and include groups and channels for prenatal and postnatal periods that appear to provide visual and textual information about pregnancy, parenting, social support, and humor. From our content analysis, we found that although a small portion of followers comment, like, and share posts, there are still large numbers of reported followers of these sites. As such, even though small portions of the network respond, these are still 606 to 12,143 unique users responding. Importantly, certain qualities of posts are associated with more user activity. Specifically, posts offering emotional support and humor are more likely to be shared, liked, or commented on. This suggests that pregnant women and mothers of babies use these popular platforms in ways that may bolster their feelings of support or help to find humor in everyday mothering or pregnancy-related themes. Research on humor has shown it to be effective in improving information retention (23,24) and health outcomes (25,26). Thus, using humor to provide health information to women around pregnancy and postnatal periods might be advantageous, since users seem to prefer humorous posts.

Other studies have found social media to be a valuable resource for seeking and receiving social support (27,28). As such, it is not surprising that followers of these Instagram channels and Facebook groups tend to be active on posts that involve emotional support, sharing and/or discussing a specific topic. This suggests that social support interventions could potentially leverage these image sharing sites to bolster social support or connect pregnant women and mothers with others experiencing similar successes and challenges.

Importantly, our content analysis provides insights into what users find unappealing or not worth liking, commenting, or sharing. Although numerous campaigns and products hire celebrities and models to promote pregnancy-related topics and items, we found that women preferred posts that tried to make pregnancy more relatable or used humor to normalize pregnancy. Also, posts that included babies in ‘awe-cute’ situations tended to not receive many comments or likes suggesting that this feature did not appeal to many followers of these pages or channels. Facebook pages often posted general pregnancy-related or baby/fetal development-related information. However, our findings suggest that these types of posts are unpopular with followers. Continually providing pregnancy information directly in posts may not have the desired effect and it may prove more useful to indirectly give that information via more humorous or relatable posts.

Finally, pregnancy- and post-partum-related posts were plentiful on the eight channels/groups we coded over a short 7-day period. As such, it is possible that users may feel overwhelmed by the sheer number of posts. The posts that were the least well received in our analysis were from sites that had the most total number of posts in a one-week period. Since activity depends on how often a user logs into the platform, the time of day the image is posted (and thus, where it is in one’s feed), the volume of posts from that channel/group (especially if it raises it on the feed), and how many channels/groups the user follows, determining what makes posts popular or unpopular is important if trying to provide health information in such a busy social media context. Previous work on the market saturation of smartphone applications suggests that users can become burdened by too many choices (18). From our results, the site with the most user attention per post tended to have the least number of total posts in a week, suggesting that in the sea of Instagram and Facebook posts, less is more.

Limitations and future direction

One limitation of the current content analysis is that postings of only four sites per platform were collected for a one-week period and thus might not reflect the true nature of pregnancy-related posts across Instagram and Facebook. While we did establish a set of criteria for the sites selected, future work sampling multiple one-week periods per site could further support our findings. Another limitation of this work is, due to the nature of social networking sites and their relative anonymity, we could only examine general interest in posts and not more specific interests (e.g., working mothers or mothers of different ethnic groups). Future work that explores the use of social networking sites as they relate to pregnancy across different groups could be fruitful in fully understanding how women are engaging with social media around their pregnancies.

This content analysis sheds light on the characteristics of current pregnancy-related social networking sites and the characteristics of posts that motivate followers into some action, such as commenting, liking or sharing. One future direction is to build off the current work to examine more closely the nature of the user comments and the conversations around pregnancy and health information that arise in the comments of posts. Is there a dialog around pregnancy information that is generated between users in the comments section of various posts?

Finally, we did not directly measure how users felt about the posts on these pages/channels. Instead, we recorded their active efforts of liking, commenting, or sharing. Future research should include pregnant women and mothers of infants’ reactions and learning from such posts.

Conclusions

This content analysis is a first step in characterizing the landscape of prenatal and postnatal information on two highly popular social media platforms. In general, these sites have large networks in which only a small proportion comment, like, or share posts. However, there are clear characteristics that differentiate the posts that garner user attention or not. This provides insights into how to provide health information and social support via social media in a way that users want to receive it. This work can inform professionals interested in leveraging Instagram and Facebook to provide pregnancy-related health information by suggesting which features are desirable. Findings also suggest that the quality of the post is more important than quantity of posts.

Acknowledgments

Funding: We gratefully acknowledge support of the National Science Foundation (NSF) through the Smart and Connected Communities (S&CC) grant (CNS-1831918).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Grimes HA, Forster DA, Newton MS. Sources of information used by women during pregnancy to meet their information needs. Midwifery 2014;30:e26-e33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewallen LP. Healthy behaviors and sources of health information among low-income pregnant women. Public Health Nurs 2004;21:200-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kraschnewski JL, Chuang CH, Poole ES, et al. Paging “Dr. Google”: does technology fill the gap created by the prenatal care visit structure? Qualitative focus group study with pregnant women. JMIR 2014;16:e147. [PubMed]

- Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. What is the impact of the Internet on decision-making in pregnancy? A global study. Birth 2011;38:336-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodger D, Skuse A, Wilmore M, et al. Pregnant women’s use of information and communications technologies to access pregnancy-related health information in South Australia. Aust J Prim Health 2013;19:308-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, et al. Pregnancy eHealth and mHealth: user proportions and characteristics of pregnant women using Web-based information sources—a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016;294:937-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tripp N, Hainey K, Liu A, et al. An emerging model of maternity care: smartphone, midwife, doctor? Women Birth 2014;27:64-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayman M, Reaburn P, Browne M, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of a web-based computer-tailored physical activity intervention for pregnant women-the Fit4Two randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soltani H, Duxbury AM, Arden MA, et al. Maternal obesity management using mobile technology: a feasibility study to evaluate a text messaging based complex intervention during pregnancy. J Obes 2015;2015:814830.

- Korda H, Itani Z. Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promot Pract 2013;14:15-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Willcox JC, Wilkinson SA, Lappas M, et al. A mobile health intervention promoting healthy gestational weight gain for women entering pregnancy at a high body mass index: the txt4two pilot randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2017;124:1718-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lau Y, Htun TP, Wong SN, et al. Therapist-supported internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e138. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ashford MT, Olander EK, Ayers S. Computer-or web-based interventions for perinatal mental health: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2016;197:134-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee EW, Denison FC, Hor K, et al. Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poorman E, Gazmararian J, Parker R, et al. Use of text messaging for maternal and infant health: A systematic review of the literature. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:969-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center, Social Media Update 2016.

- Oh HJ, Lauckner C, Boehmer J, et al. Facebooking for health: An examination into the solicitation and effects of health-related social support on social networking sites. Comput Human Behav 2013;29:2072-80. [Crossref]

- van Velsen L, Beaujean D, Gemert-Pijnen V. Why mobile health app overlad drives us crazy, and how to restore sanity. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell BE, Lewkowitz AK, Vargas JE, et al. Examining pregnancy-specific smartphone applications: what are patients being told? J Perinatol 2016;36:802-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rideout V, Foehr U, Roberts D. Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds 2010, A Kaiser Family Foundation Study: Menlo Park, CA.

- Saldaña J. Coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2009.

- Cline T, Kellaris J. The influence of humor strength and humor—message relatedness on ad memorability: A dual process model. J Advert 2007;36:55-67. [Crossref]

- Hackathorn J, Garczynski AM, Blankmeyer K, et al. All kidding aside: Humor increases learning at knowledge and comprehension levels. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 2011;11:116-23.

- Bennett MP, Lengacher C. Humor and laughter may influence health IV. humor and immune function. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2009;6:159-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bennett MP, Lengacher C. Humor and laughter may influence health: III. Laughter and health outcomes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2008;5:37-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haslam D, Tee A, Baker S. The use of social media as a mechanism of social support in parents. J Child Fam Stud 2017;26:2026-37. [Crossref]

- Lu W, Hampton K. Beyond the power of networks: Differentiating network structure from social media affordances for perceived social support. New Media Soc 2017;19:861-79. [Crossref]

Cite this article as: Oviatt JR, Reich SM. Pregnancy posting: exploring characteristics of social media posts around pregnancy and user engagement. mHealth 2019;5:46.