Barriers to HIV care and adherence for young people living with HIV in Zambia and mHealth

Introduction

Whilst overall significant progress has been made in the control and treatment of HIV, the same cannot be said for young people. The United Nations define adolescents as 10–19 years old and young people as 15–24 years old (1), the same definition will be used in this study. Despite AIDS-related deaths expeditiously decreasing in all other age groups, it is estimated there was a 45% increase in AIDS-related deaths between 2005 and 2015 amongst 15–19 year old’s (2,3). AIDS related illness remains the second highest cause of death in young females in Africa (4). In addition to young people accounting for 34% of new infections globally (2,5), UNICEF (6) has projected that, without urgent action, there will be 3.5 million new adolescent infections by 2030, with Sub-Saharan Africa being the most affected region (6).

Furthermore, in comparison to adults, adolescents and young people are less likely to be tested, access care, continue with care and achieve viral load suppression (7-10). Loss to follow up in this population is significant with 20% of young people lost to follow-up within 12 months in low income settings (3). Data on the reasons for these poor outcomes are scarce (3,11). It seems likely that potential barriers to young people accessing healthcare and treatment for HIV include: the location of the clinic, opening hours, long wait times once at the clinic, stigma, negative reactions and attitudes from caregivers, unstable guardianship and issues around the age of consent for testing and treatment, the language used by healthcare professionals (HCPs) and perceived experience of how young people were treated by them, fears around confidentiality and unintended exposure of status, delayed disclosure by parents or caregivers and mental health issues (10,12-14).

Health care systems around the world are seldom targeted at youth and adolescents and there is limited data and poor prioritization of policies and services specifically aimed at this age group (3,5,7,15-19). In Zambia in particular, it is clear that HIV services are not designed to meet the specific needs of this population (20,21).

Recognizing this need, the World Health Organization (WHO) has called for urgent, targeted research to fill established research gaps and advise adolescent HIV policies (22,23). WHO defines mHealth as the utilization of both mobile devices and wireless technologies, to assist public health and medical practices in the attainment of health objectives and suggests that mHealth may be a successful tool for improving adherence and social support for young people living with HIV (YPLHIV), given that many adolescents are already familiar with mHealth platforms and have access to mobile technology (7). It was estimated that more people in Africa had a mobile phone access than adequate sanitation by the end of 2013 (24). According to the 2015 Zambia Information and Communications Authority Report approximately 64.5%. of Zambian households have access to mobile phones and mobile phones are being actively used by 51% of individuals over 10 years old in Zambia (24). Therefore mHealth creates the potential to engage YPLHIV in care via monitoring, education, support and improved access to ART.

A growing number of mHealth applications are being implemented globally to assess their utility in improving adherence to medication and retention into care via SMS reminders, memcaps (pill bottles that register each time they are opened), appointment reminders and medication history, lab results and online support and education (25-28). Many have demonstrated the potential for opportunity within this field of health (29-31) however there is little research on specific strategies targeted at adolescents and young people (19,25,32) It may be that access to a phone is limited amongst some populations or that user cost is prohibitive, both of which must be considered a limitation of mHealth. Nonetheless, with the data available for mHealth amongst adults and the growing number of young people using mobile phones, mobile health platforms need to be investigated as a potential tool for providing YPLHIV access to accurate and unbiased information and improving adherence and retention into care for YPLHIV (5,19,33).

We explored the acceptability and feasibility of using mHealth to improve retention into care and ART adherence in YPLHIV in Zambia by engaging both YPLHIV and the HCPs that care for these populations to explore their experiences of current HIV care, their relationships with their mobile phones, their feelings around using mHealth to improve retention into care, treatment adherence and to identify barriers and facilitators to using mHealth.

Methods

Study setting

Data collection was carried out at four CIDRZ (Centre for Infectious Disease research in Zambia) supported, government-run health facilities in the Lusaka district. The CIDRZ HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment programme, at that time, supported public health facilities in four of the ten provinces of Zambia including mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) services, HIV prevention, care and treatment services, voluntary male medical circumcision (VMMC) and integrating HIV testing services into antenatal care and TB disease screening and treatment programmes.

Study population and recruitment

Young people were eligible if they met the inclusion criteria of (I) being 16–24 years old, (II) living with HIV, and (III) currently receiving care at participating site. HCPs were eligible if they were either a (I) HCP in HIV care working with YPLHIV in CIDRZ-supported health centres, or (II) a peer support worker (PSW) working with YPLHIV in CIDRZ health centres. Participants were excluded if they were unable/unwilling to give informed consent.

Purposive sampling was used and eligible participants were identified by the PSWs and clinical team at the listed health facilities, from patients known to them at the time. Potential participants were approached either face-to-face or via telephone. Those interested were provided with a date and time that the researcher would be on site. Prior to data collection commencing participants were provided with a participant information sheet, detailing the purpose of the research. Once this had been read and discussed, and any questions answered, informed consent was received. In addition to YPLHIV and HCPs who work with the YPLHIV, PSWs were also recruited as members of this group are often YPLHIV and also work closely with the HCPs at the health facilities. Therefore, they provide a unique perspective. Participants were reimbursed their travel expenses.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection was carried out at focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs). FGDs were used for the YPLHIV as an effective way of gaining a larger viewpoint in a shorter amount of time. IDIs were used for PSWs and HCPs as it was felt these participants may be more limited by time constraints. Additionally, it was anticipated that PSWs may have had a different viewpoint to YPLHIV, as they both accessed the HIV-services and worked within them; the decision to use IDIs for the HCPs was also guided by prior experience amongst this specific population which showed that HCPs responded better to IDI’s than FGDs (in house communication with CIDRZ qualitative researchers). To avoid stifling this process, semi-structured question guides were used, which were guided by previous HIV, adolescent and mHealth research. These were separated into two categories focusing on barriers to HIV care and retention and mHealth. Open-ended questions were used, in an endeavor to gain a more in-depth response.

FGDs were conducted in both English and local languages and the IDIs in English. The FGDs lasted around 90 minutes and the IDIs no longer than 30 minutes. FGDs were conducted by a local researcher, who is experienced in conducting FGDs and IDIs. IDI’s were conducted by the non-local primary investigator with assistance from the local investigator. All data collection was carried out in private rooms at the health facilities and two audio-recording devices were used. There was no one else present other than the researchers and participants. Where participants responses were inaudible this was documented in the transcripts, although this was minimal. All participants were allocated a unique patient identifier (UPI) which was never stored in conjunction with their name and all were stored securely. Identification on audio and electronic transcript was only via UPI and audio recordings were destroyed once they had been transcribed. Signed informed consents were maintained separately in a locked cabinet.

Transcription of the FGDs was carried out by an in-country translator. Transcripts were entered into NVivo software and were subjected to a process of open coding, axial coding and memo writing followed by the development of key concepts and categories as described by Braun and Clarke (34). This was all carried out by the principal researcher.

Regulatory approval and ethical considerations

Ethical approval was gained from the BSMS Research Governance and Ethics Committee [ER/BMS9AVH/1], University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee [007-05-18] and consent to proceed from the National Health Research Authority Zambia.

Whilst the risk to participants was perceived as minimal, there was a possibility of distress to patient participants caused during IDIs or FGDs. This was addressed by explaining the possible risks in the participant information sheet (PIS), ahead of taking part in the study. It was not expected that distress should occur as the focus was not on the participants HIV status, but their experience of the services available to them and their mobile phone use. However, in the event that a participant should become distressed additional sources of support were included in the PIS. All FGDs and IDIs took place in the participants’ usual place of care and by invitation only and therefore the risk of unintended disclosure was minimal.

Results

Three FGDs were conducted with a total of 24 participants, aged between 16–23 years (median =19, range =7, 54% male). 28 in total presented to the FGD sessions, but 4 were excluded due to being outside the age range. One reported being at university, 13 as grade 12 school leavers, four in grade 12, one in 11, one in ten, two in nine, one in seven and one participant declined to answer their education status. Six IDIs were carried out, three HCPs and three PSWs. The HCPs each had between 12–18 years’ experience working in a healthcare setting.

Experiences and perceived barriers to HIV care of YPLHIV currently engaging with HIV Care and HCP

Stigma

The YPLHIV participants were asked about their perceptions and experiences of accessing HIV care in Lusaka, Zambia. Many of the YPLHIV described the difficulties they faced in relation to stigma and discrimination. The YPLHIV suggested very little has improved in regards to stigma and discrimination in Zambia.

“Sometimes we have discrimination at schools or maybe in the homes where we come from. We have that discrimination; our friends discriminate us since they know that that one is positive. They now discriminate themselves saying that one should be playing on her own and us we will be alone.” (F1,4)

Across all FGDs YPLHIV reported experiencing perceived stigma and stigma itself when going for treatment or collecting medication, suggesting this served as a barrier to accessing HIV care for many. They felt that due to a separation of HIV services from other services, people would know why they were at the clinic. Once they join the queue for ART then others at the facility would know their status and treat them differently. All of which they felt contributed to creating self-stigma in some and could cause young people to withdraw from treatment.

“What I feel is these young people maybe it's because when they want to seek HIV care, they find that in the clinics there is, we don't have clinics which like separates them to say that they should be on their own. They are mixed with the adults and that the compound where they come from, they know their neighbors and friends. So when they come to the clinic maybe they want to seek that help. You'll find that she sees neighbor and then they are somehow withdrawing.” (I2,HCP)

Long wait times at clinics

Long wait times at clinics were reported as a negative experience for the YPLHIV and something they believed stopped others coming for care. They also felt that the HCPs did not consider their feelings, often leaving them waiting (unnecessarily).

“The time the staff come, they don’t come in time, they come and first make breakfast, chat, so like that time goes. When its 12:00 they will make sure they leave their offices, they go and have lunch us we are starving. Some of us have appetites we need to be eating but with them they will leave you on the line just there, they go out they leave you just like that.” (F1,6)

Experiences with HCPs

The treatment of YPLHIV by the HCPs also impacted on access to HIV services. They felt the HCPs did not understand them or their needs and that they were spoken to in an inappropriate manner or scolded. When spoken to badly they wanted to leave and not return. Some reported that after being shouted at they just left and went back to school, without collecting their medication.

“One of my experiences, is maybe sometimes you find that young people, adolescents go to school, they come in the morning to come and ask for help from the nurse or the doctor and then that nurse maybe shouts at the young girl saying just be in the line instead of helping her so that she goes to school, but they start like shouting again, shouting at her. So that’s the bad experience that I have seen.” (F1,4)

The HCP also agreed that if a YPLHIV had an unpleasant interaction with a HCP whilst at the clinic they may leave and not return.

Education

A lack of education around HIV and treatment was cited as a reason for poor retention into care and drug adherence. Several YPLHIV reported that they felt others do not know the importance of why they need to take the medication. Some felt if there was more education it would empower YPLHIV to overcome the stigma they face, with the overall consensus being that an increase in education would result in an improvement of retention into care.

The PSWs also believed that a lack of HIV knowledge was a barrier to care and adherence. Young people may withdraw from care as they struggle to come to terms with their HIV positive status, due to a lack of understanding about how they became positive.

Clinic hours

Difficulties in attending the clinics during the opening hours were expressed amongst the groups as it meant them missing school often. This was of particular concern as they felt that due to the way the government schooling works in Zambia, they were missing out on a lot of education whilst they attend the clinic. They believed that others decided not to attend at all.

Lack of support

YPLHIV with a poor support network said they felt isolated and alone. This impacted negatively on their mental wellbeing and could result in poor adherence. Some stated the lack of support started at home and that this was particularly true when living with caregivers or guardians. If they felt negatively about themselves and their condition then they were less motivated to do well.

Experience of using mHealth

It was suggested by HCPs that patients found it easier to communicate with them via their phones. Reporting that patients would message them after a face to face consultation to ask questions they felt too embarrassed to ask in person. The HCPs used their phones to contact patients when they were far from the health centre, to encourage them to adhere and monitor how they were feeling. The YPLHIV reported that in the past HCPs had sent text messages to remind them to take their medication and give them advice on disclosure and looking after themselves.

Many of the young people participants were engaged in WhatsApp or Facebook groups, specifically for HIV positive young people, where they were able to discuss positive living and sexual reproductive health (SRH). As well as having several health-related apps to get information about their well-being. Of concern though was that the young people in the study reported using websites to self-diagnose when they were unwell and even an app that you place your finger on and displays whether you are HIV positive.

Acceptability and perceptions of using mHealth within HIV services for YPLHIV

It was felt unanimously that mHealth would be an acceptable and beneficial adjunct to HIV services for YPLHIV. Specifically, mHealth would be a useful tool to reach them and help retention into care and adherence. Study participants felt by giving the young people knowledge about their own condition via mHealth it would empower them to take control over their treatment.

“It can be helpful to help the young people, because most of them these young people they are used to mobile phones. If you go to schools or homes, they are using mobile phones. So it would be helpful, young people would benefit.” (I1,PSW)

The reasons for participants believing mHealth to be beneficial were an extension of what they would like to see included in an app or SMS service. As such we attempted to explore what contents the participants felt were necessary, so that mHealth may improve retention into care and adherence for YPLHIV in Zambia.

Education

Echoing what participants said about a lack of knowledge resulting in poor adherence, the participants felt that it would be very beneficial if the app could provide education about HIV and ART.

“For young people living with HIV to use the mobile phone doesn’t ah it will not be like a difficult thing, yeah. It’s a very easy thing. As I said earlier it will give them hope, yeah it will give them hope to give them more knowledge about HIV and ART. So it will be very useful for them, yes. Very easy for them.” (I3,PSW)

They believed this would not only improve adherence but also assist in dispelling the myths that exist around HIV. The inaccurate beliefs that surround HIV and the lack of understanding of the importance of ART was cited as reasons for poor adherence and therefore the young people felt being better informed via mHealth would improve adherence.

Lab results

Both YPLHIV and HCPs felt providing lab results would improve engagement with care. HCPs reported having some inquisitive patients, but they do not always have access to the results when seeing the YPLHIV in the clinic or the young people do not always think to ask, but if they were seeing them regularly on the app, then it may encourage them to take their medication and try to improve their results. The young people expressed difficulty in accessing results, often being told they are not available. They echoed the HCPs in that seeing their results would encourage them to do well.

Online forum

Access to an online forum was felt throughout participants to be vital in the app. Support featured frequently as an important factor to good adherence. Therefore, participants felt if they could access an online forum anonymously they would feel more comfortable to ask questions and to seek and provide support to others. Study participants described how by sharing their stories and giving feedback to others it would benefit their mental wellbeing, knowing that they are not the only ones living with HIV.

Appointments and medication reminders

By having access to appointment times, it was felt it would serve not only as a reminder to attend, but also reduce travel costs for some YPLHIV. Some attend on incorrect days, spending unnecessary money on travel. Consequently in the future they feel if they can’t remember when their appointment is, they will just not go at all.

Medication reminders were highlighted as important. Reasons noted for this were it can be easy to forget, particularly if you are away from home or newly diagnosed and feeling supported.

Drug refill

It was perceived by the YPLHIV and HCPs that incorporating drug refill requests into an mHealth app would be of benefit, as it may decrease some of the waiting times at clinics.

Barriers and facilitators to using mHealth amongst YPLHIV in Zambia

Some YPLHIV commented that individuals may not prioritize data usage to engage with the app. Conversely, not all thought that free data would provide the solution. The YPLHIV participants were divided on the issue of whether data would be used for the app with others believing if the app met their needs, they would be very happy to use their data for it.

A concern expressed by the young people was the language of the app or SMS. There are many languages spoken in Zambia and some felt some of their peers may not speak English well enough to engage and that it may lead to them misinterpreting its contents. Misinterpretation was also a concern in relation to lab results. It was felt by some that not all young people would have the capacity to understand them, without a HCP present to explain.

Confidentiality was cited as a major concern that may prevent some from engaging with mHealth. Incidences were discussed where the YPLHIV had engaged with online HIV related discussions in the past and someone else had taken a screen shot of the discussion and circulated it, exposing their HIV status.

Another facilitator suggested was providing free data or talk time in return for engaging with the app, believing that people may join initially for the reward but will continue to engage once they discover the benefits.

Discussion

Participants unanimously felt mHealth solutions would be beneficial in improving retention into care and ART adherence in YPLHIV in their settings. The overarching barrier to HIV care as perceived by the YPLHIV was stigma, a theme that ran through many of the other barriers reported. Encountering stigma whilst in healthcare queues was also seen in a study focused on people living with disabilities in Lusaka (35) Our findings support previous work which suggested that HIV-related stigma was the main reason people were reticent to engage in treatment (36).

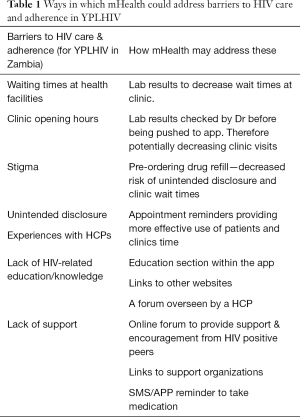

All participants reported using phones mostly for social media, internet and communicating with friends. Both YPLHIV and HCPs reported using their phones for support in regards to living with HIV or advice about particular patients. Experience of using mHealth to improve retention into care of YPLHIV was not a concept that our respondents had encountered, although it was felt unanimously that it would be of benefit. The YPLHIV presented innovative ways in which they were using their mobile phones for health-related purposes, seeking to bridge the gaps in healthcare (Table 1). Hampshire et al. (37) report similar findings and termed this informal mHealth.

Full table

All participants felt targeted education should be included. In this study, lack of HIV education was posited as an important reason that young people were unable to accept their status, did not engage in HIV care and had poor adherence. Poor HIV knowledge is often referred to in relation to stigma, health-beliefs and low-education levels in general (38,39). However the participants in our study felt strongly that this was a stand-alone reason serving as a barrier to HIV care and adherence. As such this study suggests that providing information and education via mHealth could serve as a powerful tool in disease prevention and management, as supported by other mHealth research (40,41).In some cases participants reported using phones as a diagnostic tool, rather than attending a health clinic or an app that diagnoses HIV using the finger—highlighting the need to work with young people to create regulated, formal mHealth platforms (37).

Barriers to HIV care and adherence in this study were cited as negative experiences with HCPs, poor support structures, fear of unintended status disclosure and long wait times at clinics. Participants felt mHealth supported pathways could address these via access to lab results, an online forum, appointment and medication reminders and requests for drug refills. It has been shown that in patients that are stable on treatment, reduction in frequency of clinic visits and medication collection and streamlining clinic care so that patient visits are shorter resulted in an improvement in treatment adherence (4,42), all of these could be addressed via mHealth. A systematic review of YPLHIV from key populations demonstrated some encouraging results in adherence and viral load when using mHealth (19). Whilst the desirable functions for an mHealth app requested by the YPLHIV have been shown to be beneficial in other HIV research (43), much of this research is in adult populations and so does not take into account the specific barriers adolescents and young people face and therefore is not generalizable to our study group. Some studies do conclude however that medication reminders have been shown to improve ART adherence in adults (25,44) Therefore a logical next step would be to see if the same can be seen in young people.

To increase engagement with mHealth participants felt it would be better if the app could be free to use or if they could be given free talk time in return for engaging with the app. It was also suggested the app should be reliable and fast, as slow responses had caused the young study participants to stop engaging in other mHealth. As all of our participants were accustomed to using mobile phones the acquisition of new skills would not be required, but general consensus was that workshops demonstrating how the app would work, would serve as a facilitator to implementation and this desire to learn is a promising sign.

Barriers to engaging with mHealth were based around fear of confidentiality and language used, issues that have also been identified elsewhere (45,46). Therefore, it is imperative when designing a platform that it is done alongside YPLHIV, to understand the issues they have encountered with confidentiality in the past and to create a secure mHealth platform to ensure they do not have the same experiences in future. It was suggested that if the mHealth platform was in English and their grasp of the language was limited this may lead to misunderstanding of the information. These type of usability issues have also been reported in other studies (45,47). Due to the amount of languages spoken in Zambia this would appear difficult to overcome and should further mHealth research be undertaken in the form of an app or SMS, care should be taken to ensure that the participants have a sufficient understanding of the language used. It also highlights the importance of co-design when developing an mHealth platform, to ensure the language used is representative of its target audience and perhaps could be supported by graphics to increase usability. What this study demonstrates alongside others is that as mobile phone coverage increase young people are not waiting for formal mHealth platforms to come to them, rather they are developing their own informal mHealth in an attempt to secure healthcare and support (37). Therefore, demonstrating that the concept of mHealth is an acceptable and feasible adjunct to try to decrease barriers to HIV care and adherence in YPLHIV.

A limitation of the data collected is the variation in interviewer. The focus groups were conducted by a translator and the IDIs were conducted by the principal researcher. Therefore, interview styles differed between interviewers. To avoid the possibility of power or social relations impacting on the group results (48) or some participants not feeling comfortable talking openly, IDIs were also offered to the YPLHIV. All analysis of the data was conducted only by the PR hereby limiting differential bias during analyses.

The intention of the study was to conduct three FGD, with ten YPLHIV participants in each. Ultimately four were excluded across the groups due to them being outside the specified age range. This may have altered the richness of the data, but as the FGD largely resulted in similar results across all three, the impact is felt to be minimal. Saturation point was also intended across the study but as the HCP IDIs were made up of three peer-support workers and three nurse-practitioners working with the YPLHIV, data saturation was not achieved amongst the nurses. This was due to time constraints and given more time an increased amount of IDIs may produce a fuller data set as their perceived barriers to HIV care for YPLHIV differed to each other and the YPLHIV.

The sample used has potential for bias as it was a sample chosen from a specific clinic database within urban areas. The strengths of the sample group however are that they are closely linked to the aims of research and are already involved in treatment and care of YPLHIV. Whilst it would be beneficial to recruit YPLHIV who do not engage with HIV care or live in more rural settings in similar research in future, it is obvious that our findings support the feasibility and acceptability of using mHealth amongst adolescents. This data can and should contribute significantly to the design of future studies of YPLHIV and the development of suitable mobile applications.

Conclusions

HIV-related stigma, long wait times, restricted opening hours and negative experiences with HCP’s remain major barriers to accessing care for YPLHIV. Implementing strategies that ensure health facilities are more adolescent friendly via opening times, specifically trained staff and a more confidential environment need to be addressed. However with the growing access to mobile phones and the internet, mHealth based solutions may play a vital role in providing YPLHIV with information, psychosocial support and by reducing time spent at health facilities leading to not only improved health outcomes but possibly also cost and resource benefits via task-shifting, education and more effective use of clinical appointments. mHealth demonstrates potential for improving adherence and support but there is a lack of evidence, particularly around adolescents and young people. Research that is designed alongside adolescents and young people is imperative to allow mHealth to realize its full potential, and as such more research is urgently needed to explore these possibilities.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by core funding from Brighton and Sussex Medical School (Rising Starts Grant, University of Brighton F002-18).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by BSMS Research Governance Ethics Committee [ER/BMS9AVH/1] and The University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee [007-05-18]. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- United Nations. Definition of Youth [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 17]. Available online: http://undesadspd.org/Youth.aspxfacebook.com/

- UNAIDS. Data 2017. Program HIV/AIDS [Internet]. 2017;1–248. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf

- UNAIDS. Ending the AIDS epidemic for adolescents, with adolescents A practical guide to meaningfully engage adolescents in the AIDS response. [cited 2018 Jun 14]; Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ending-AIDS-epidemic-adolescents_en.pdf

- UNAIDS. Ending Aids Progress Towards the 90-90-90 Targets. Glob Aids Updat 2017;198. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/Global_AIDS_update_2017_en.pdf

- McCarraher DR, Packer C, Mercer S, et al. Adolescents living with HIV in the Copperbelt Province of Zambia: Their reproductive health needs and experiences. Harrison A, editor. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197853.

- UNICEF. Children and AIDS Statistical Update. 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 14]; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/HIVAIDS-Statistical-Update-2017.pdf

- World Health Organization. HIV and Adolescents: Guidance for HIV Testing and Counselling and Care for Adolescents Living with HIV. Recommendations for a Public Health Approach and Considerations for Policy-Makers and Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, et al. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2013;17:86-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eba PM, Lim H. Reviewing independent access to HIV testing, counselling and treatment for adolescents in HIV-specific laws in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for the HIV response: Implications. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21456. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nabukeera-Barungi N, Elyanu P, Asire B, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for adolescents living with HIV from 10 districts in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:520. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong VJ, Murray KR, Phelps BR, et al. Adolescents, young people, and the 90–90–90 goals. AIDS 2017;31:S191-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mburu G, Ram M, Oxenham D, et al. Responding to adolescents living with HIV in Zambia: A social-ecological approach. Child Youth Serv Rev 2014;45:9-17. [Crossref]

- Kung TH, Wallace ML, Snyder KL, et al. South African healthcare provider perspectives on transitioning adolescents into adult HIV care. S Afr Med J 2016;106:804-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bekker LG, Hosek S. HIV and adolescents: focus on young key populations. Int Aids Soc 2015;18:20076.

- Pettitt ED, Greifinger RC, Phelps BR, et al. Improving Health Services for Adolescents Living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multi-Country Assessment. Afr J Reprod Health 2013;17:17-31. [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. Prevention Gap Report 2016. Vol. 83, UNAIDS. 2016. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf

- Adejumo OA, Malee KM, Ryscavage P, et al. Contemporary issues on the epidemiology and antiretroviral adherence of HIV-infected adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A narrative review. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:20049. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- UNICEF, UNAIDS. A Progress Report All In To End The Adolescent AIDS Epidemic. 2016. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/aids/files/ALL_IN_2016_Progress_Report_6_16_17.pdf

- Lall P, Lim SH, Khairuddin N, et al. Review: an urgent need for research on factors impacting adherence to and retention in care among HIV-positive youth and adolescents from key populations. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:19393. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Zambia National Health Strategic Plan 2017 – 2021. 2017. Available online: http://www.moh.gov.zm/docs/ZambiaNHSP.pdf

- Association of Chartered Certified Accountants. Key health challenges for Zambia. 2013; Available online: https://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/acca/global/PDF-technical/health-sector/tech-tp-khcz.pdf

- Armstrong A, Nagata JM, Vicari M, et al. SUPPLEMENT ARTICLE A Global Research Agenda for Adolescents Living With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78:16-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Global Research Agenda for Adolescents Living With HIV. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/toolkits/cipher-research-adolescents-living-with-hiv/en/

- Banda B, Siluyele I, Lwao E, et al. ICT Survey Report-Households and individuals survey on access and usage of information and communication technology by households and individuals in Zambia [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Jul 29]. Available online: https://www.zicta.zm/Views/Publications/2015ICTSURVEYREPORT.pdf

- Betjeman TJ, Soghoian SE, Foran MP. mHealth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Telemed Appl 2013;2013:482324.

- World Health Organization. mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies. Observatory 2011;3:66-71.

- Lewis MA, Uhrig JD, Bann CM, et al. Tailored text messaging intervention for HIV adherence: a proof-of-concept study. Health Psychol 2013;32:248-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rana Y, Haberer J, Huang H, et al. Short Message Service (SMS)-Based Intervention to Improve Treatment Adherence among HIV-Positive Youth in Uganda: Focus Group Findings. Clark JL, editor. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125187.

- Forrest JI, Wiens M, Kanters S, et al. Mobile health applications for HIV prevention and care in Africa. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015;10:464-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Jan CB, Mohutsiwa-Dibe N, Loukanova S. Systematic review on what works, what does not work and why of implementation of mobile health (mHealth) projects in Africa. BMC Public Health 2014;14:188. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Purnomo J, Coote K, Mao L, et al. Using eHealth to engage and retain priority populations in the HIV treatment and care cascade in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bain LE, Nkoke C, Noubiap JJN. UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: comment on “Can the UNAIDS 90–90–90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades.” BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000227. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- L’Engle K, Plourde KF, Zan T. Evidence-based adaptation and scale-up of a mobile phone health information service. mHealth 2017;3:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101. [Crossref]

- Parsons JA, Bond VA, Nixon SA. “Are We Not Human?” Stories of Stigma, Disability and HIV from Lusaka, Zambia and Their Implications for Access to Health Services. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127392. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. Reduction of stigma and discrimination [Internet]. 2014. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/en/ourwork/programmebranch/

- Hampshire K, Porter G, Owusu S, et al. Informal m-health: How are young people using mobile phones to bridge healthcare gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa? Soc Sci Med 2015;142:90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao D, Kekwaletswe TC, Hosek S, et al. Stigma and social barriers to medication adherence with urban youth living with HIV. AIDS Care 2007;19:28-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mburu G, Hodgson I, Kalibala S, et al. Adolescent HIV disclosure in Zambia: barriers, facilitators and outcomes. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:18866. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev 2010;32:56-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vahdat HL, L’Engle KL, Plourde KF, et al. There are some questions you may not ask in a clinic: Providing contraception information to young people in Kenya using SMS. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123:e2-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buzaalirwa LE, Maharaj T, Kgaka N, et al. Strategies to Address Clinic waiting time and Retention in are Lessons from a large ART centre in South Africa Background to (PDF Download Available). Conference: ICASA, At Capetown - South Africa 2013.

- Cooper V, Clatworthy J, Whetham J, et al. The Open AIDS Journal mHealth Interventions To Support Self-Management In HIV: A Systematic Review. Open AIDS J 2017;11:119-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seidenberg P, Nicholson S, Schaefer M, et al. Early infant diagnosis of HIV infection in Zambia through mobile phone texting of blood test results. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:348-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smillie K, Van Borek N, van der Kop ML, et al. Mobile health for early retention in HIV care: a qualitative study in Kenya (WelTel Retain). Afr J AIDS Res 2014;13:331-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conserve DF, Jennings L, Aguiar C, et al. Systematic review of mobile health behavioural interventions to improve uptake of HIV testing for vulnerable and key populations. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:347-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurupur VP, Wan TTH. Challenges in implementing mHealth interventions: a technical perspective. Mhealth 2017;3:32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matthews B, Ross L. Research methods a practical guide for the social sciences. Essex: Pearson Education Limited; 2010.

Cite this article as: St Clair-Sullivan N, Mwamba C, Whetham J, Bolton Moore C, Darking M, Vera J. Barriers to HIV care and adherence for young people living with HIV in Zambia and mHealth. mHealth 2019;5:45.