“I Feel Like A Neurotic Mother at Times”—a mixed methods study exploring online health information seeking behaviour in new parents

Introduction

In contemporary society, due to the exponential growth of technology and the online platform, data acquisition has never been so effortless (1). In Western society especially, if an individual has a query which requires resolution, the answer is merely seconds away, more oft than not, within the palm of one’s hand. Technology has bridged a gap between professionals and laities, allowing the general population to retrieve and analyse material which was once only accessible in the professional and academic fields (2). This is especially salient when considering online health information as data evinces that this is the predominant topic searched online (3). Subsequent accessibility to health information has been reported as having many positive and negative effects (4,5). Whilst the online platform facilitates uncomplicated access, community and a sense of belonging and anonymity, it has been intrinsically linked to invalidated information and increased health anxiety (6-8).

Health anxiety is the apprehension of experiencing or developing an ailment due to symptomology misinterpretation (9,10). Symptoms of, and health anxiety itself, are to be considered on a continuum as opposed to constrained by strict, clinical diagnostic criteria as they can vary from mild to clinically valid worries (11-13).

One such lifetime occurrence which causes increased anxiety is becoming a new parent. Adapting to the role of a new parent necessitates a paramount shift in the customary way in which one may live their life. Roles, responsibilities, relationships, expectations and personal morals are just some of the aspects of life which will be subjected to alteration. Becoming a new parent can be the causal factor of unprecedented stress and anxiety in regards to parental ability and the health of one’s child. New parents often use the online platform to seek information which will educate them on how best to care for their child and to keep their child’s health at the optimum level (5,14,15).

A larger scale, mixed methods study, recruited participants who were pregnant or had recently become new parents to explore significant predictors of health anxiety whilst searching online for health information. The results published from this study focused solely on pregnant women (5,16). From the responses, the quantitative results (5) evidenced that health anxiety during pregnancy elevated when medical complications had been experienced in a previous pregnancy and if under medical treatment for a non-pregnancy related condition. The skill of, when searching online for health information, being able to recognise when one had enough information, and repeating searches were also significant predictors of health anxiety. The qualitative results suggested that pregnant women found reassurance from others, gaining a decreased sense of isolation and normalising their pregnancy symptoms (16).

Aims & objectives

The data analysed was extracted from the larger scale study, focusing solely on data provided by new parents. The study aims to examine the effects of previous illnesses and frequency of online health information searches on levels of health anxiety. The quantitative data explores predictors of health anxiety focusing on the following four hypotheses:

- H1: Medical complications in previous pregnancies will be a significant predictor of health anxiety;

- H2: Having been under medical care and supervision for a temporary or chronic health condition within the last year will be a significant predictor of health anxiety;

- H3: The frequency in which a new parent searches for health information for their self will be a significant predictor of health anxiety

- H4: The frequency in which a new parent searches for health information for their child will be a significant predictor of health anxiety.

In contrast the qualitative aspect of the study explores why new parents turn to the online platform for health information.

Methods

The larger scale study from which this data is extracted, used both interviews and questionnaires on pregnant participants and questionnaires on new parents. This paper will focus solely on the questionnaires completed by the new parents.

Ethics

Approval for the study was given by University of Bolton Research Ethics Committee in October 2015, United Kingdom.

Materials

The online Pregnancy Questionnaire used within this study was inclusive of the Short HAI Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI) (17). The questionnaire was tailored for both pregnant women and new parents. Further questions explored how new parents use the internet to seek health information online and whose health they used it in relation to. Questions explored why the online platform was used and what positive and negative consequences, if any, were experienced in the process.

Recruitment procedure

The research was disseminated and advertised on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and a purpose-built website named “A Healthy Search” which provided all information relevant to the study and participation. The study was electronically sent to pregnancy and new parent organisations such as NCT (National Childcare Trust), BabyCentre, Anatomy Manchester, Baby Ultrasound Clinic, Life Designs and More, Totally Holistic Health, Mamafit, Misfit Mamas, Wellbeing of Women, St. Brendan’s Nursery, Go Create ‘Messy Play’, Funtastic, John Krantz Psychological Research, Embrace Birthing. Hard copies of the questionnaire were also provided to the aforementioned organisations. In turn, these organisations shared the study information on both online and offline platforms (5).

Data analysis

Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS software version 25. Data were tested for normality and a regression was used to explore significant predictors of health anxiety in new parents.

The qualitative data was thematically analysed using Nvivo version 10 software. A thematic analysis method was employed to analyse the new parent discourse. This method was deemed most appropriate as the results would be extracted from the data using Braun and Clarkes [2006] approach to thematic analysis to establish and maintain inter-coder reliability the data was coded by two authors.

Results

An analysis of standard residuals was carried out on the data to identify any outliers, which indicated that participant 7 needed to be removed. After the outlier was removed from the data a second analysis of standard residuals was carried out, which showed that the data contained no outliers (Std. residual min =−1.50, Std. residual max =3.25). The data was tested for, and evidenced normality.

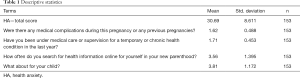

A multiple regression was run on the data to see if, medical complications in pregnancy, medical care within the past year, frequency of searching online for self and frequency of searching online for child predicted levels of health anxiety (Table 1).

Full table

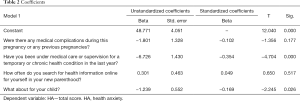

It was found that medical complications in pregnancy, medical care within the past year, frequency of searching online for self and frequency of searching online for child explain a significant amount of the variance in levels of health anxiety [F(4,149) =7.61, P<0.01, R2 =0.41, R2adjusted =0.15] (Table 2).

Full table

The analysis shows that medical complications in pregnancy did not significantly predict health anxiety [β =−0.10, t(152) =−1.36], however medical care within the past year did significantly predict health anxiety [β =−3.54, t(152) =−4.70, P<0.01]. It can also be seen that frequency of searching online for self, did not significantly predict health anxiety [β =0.049, t(152) =0.65], yet searching online for child did significantly predict health anxiety [β =-0.17, t(152) =−2.25, P<0.05].

As aforementioned, the data has been derived from a larger data set and a larger scale study which posed the same questions to pregnant women as well as new parents. The previous study reported that pregnancy is a specific predictor of health anxiety due to the various somatic symptoms which a woman experiences during this time (5).

However, the analysis of the new parent data has evidenced that any complications within pregnancy, or previous pregnancies, does not significantly affect levels of health anxiety in new parents. Yet, having been under medical care or supervision for a temporary or chronic health condition within the past year does have a significant effect on health anxiety for new parents. This suggests that, whilst medical complications within pregnancy do not have a lasting effect on levels of health anxiety, general or chronic non-pregnancy related issues do. This could be due to the fact that the health issues they are experiencing which are non-pregnancy related are ongoing, as opposed to occurring within the 9-month gestation span.

The previous study, found that the frequency in which pregnant women searched for health information online for themselves had a significant effect on levels of health anxiety, but not the frequency of searching for their child (5). Juxtaposed to this, the results, when posed to new parents instead of pregnant women show the opposite. This evidences that, now no longer pregnant, women are searching solely for their child as they are no longer carrying them. This implies that any levels of health anxiety that a pregnant woman experience in regards to their health are transferred to their child upon arrival. This could lead to new parents possibly overlooking their own symptoms and health conditions as the onus is no longer upon their selves.

Two main findings were extracted from the qualitative data. This was the fact that when new parents search online for health information, they are either seeking for their selves or for their child. In regards to the child, two themes were found. The first was child development, which had no subtheme and the second was informed parenting which had three subthemes; inexperience and normalisation. In regards to the parent, three themes were found; healthcare avoidant behaviour, support and anxiety. The subthemes of healthcare avoidant behaviour were anonymity and avoiding judgement. The subthemes for support were emotional and informational and the subthemes for anxiety were an increase and reduction in the emotion. The themes and subthemes are presented in Table 3.

Full table

Child

New parents are often prompted to search online for health information for their child. The causal effect for this may be general information acquisition. A new parent may experience the want to know more and further educate themselves on the optimum methods of parenting. This could be in relation to a plethora of aspects, for example, breast feeding, skin to skin contact or sleeping techniques. Another trigger for health information seeking for one’s child could be a symptom which has been displayed and observed which has become a cause for concern to the new parent.

Child development

It is not uncommon for new parents to experience concern over their child’s development. New parents mentioned that they searched online for how typical their child’s development is. This included illness, feeding issues and developmental milestones.

Although the relevant healthcare professionals such as general practitioners, midwives and health visitors advise that each and every child will develop and grow at their own pace, the issue remains a significant concern for new parents (18). In the UK, there are statutory government guidelines in place for child development such as the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework, which suggests stages a child should progressively be developing towards in relation to their age (18). However, new parents have the potential to put too much onus upon the age restrictions of these stages and compare their own children’s development to others. If it appears that their child is developing at a slower rate than others, nor meeting the suggested guidelines, then this could potentially lead new parents to believe that their child is not progressing as it should be. This can cause a new parent to present with undue concerns regarding their child’s health and increase levels of health anxiety.

Informed parent

Having a child is one of the most major transitions in life and it requires a new focus. Parents need to adapt and learn about new roles and experience a reorganisation of their lives (19).

Inexperience

The inexperience a new parent may feel when their child comes into the world can cause them to second guess their actions and experience a sense of failure and self-doubt in reference to their own parenting capabilities. This is one of the reasons that a new parent will seek information online.

“I don’t always know what I’m doing and all babies are different so web forums give a wider pool of experience”—Participant 109

“The Unknown! I.e., things I don’t know I should be worrying about!”—Participant 119

New parents can oft feel unequipped of the skills and information needed when becoming responsible for a child. Inexperience in regards to becoming a parent can be considered typical due to the drastic changes in one’s circumstance. Normal fears can be defined as a typical reaction to real or perceived dangers and is ruminated to be an adaptive and integral facet of development which primarily promotes survival (20). Some participants had had minimal contact with babies in general before giving birth and therefore, lacked experience. Inexperience of new parents also instigated online searches.

Normalisation

For some new parents, knowing that the feelings that they are experiencing or the symptoms which their child is experiencing are typical can provide a salient sense of reassurance. This method of searching information online affirms the typicality of new born babies for new parents.

“More of the ‘is this normal’ type”—Participant 127

“I will ask fellow mums advice to see if their child has had similar issues”—Participant 49

Also, for new parents, to be aware that they are not the only ones experiencing difficulties within their situation can be just as crucial as discussing solutions to said difficulties as it provides a sense of comfort and normality.

“When more parents had the same kind or worries and they put you at ease with what they did and what helped”—Participant 4

This method of online socialisation may not just provide new parents with information regarding the typicality of a new-born’s health, but also eradicate feelings self-doubt and bad practise in parenting.

Parent

Healthcare avoidant behaviour

Some new parents searched health information online due to health care professional avoidant behaviour.

Anonymity

New parents turned to the online platform for an increased level of anonymity due to how professionals may perceive themselves as parents or their queries.

“(Online) you feel comfortable asking stupid questions”—Participant 91

“I feel like a neurotic mother at times and too embarrassed to appear like a pushy mum to GP”—Participant 111

Amongst the new parent cohort, there was an overarching subtheme of concern regarding the discernment of their aptitude to decipher whether their child’s health was below optimum, therefor the anonymity that the online platform granted was preferred as opposed to face to face interaction.

Avoiding judgement

There was an emergent subtheme which suggested that new parents felt they were wasting the time of health care professionals when they contacted or made appointments with the relevant services.

“You can remain relatively anonymous on line and feel less like an overanxious parent”—Participant 115

Some new parents can feel somewhat inadequate when interpreting their child’s symptoms and do not want to be perceived as over reacting. The fear of judgement seems to derive from a fear of self-doubt as a new parent. New parents tend to feel as though they are wasting a healthcare professional’s time if they take it up with symptoms which could quite possibly be typical or menial. This can cause an avoidant type behaviour. Whilst an overuse of healthcare services and professional’s time is unnecessary and can place a strain on services, under usage can also be dangerous, as underlying symptoms or illnesses may not be observed or diagnosed. New parents also display concern about a healthcare professional’s perception of them. They tend to display avoidant behaviours so that they are not judged, become embarrassed or feel as though they are being spoken down to.

Support

Previous empirical studies show that new parents, female more than male, are inclined to experience acute episodes of anxiety concerning their competency as a parent immediately postpartum (21,22). New parents stated that sometimes, their reason for turning to the online platform for information was to search for information or confer with others on the topic of parenting techniques.

Emotional

New parents access the online platform to gain advice from other parents, whether this is; general questions, information, tips and/or techniques. The online platform was also used as support when new parents felt lonely and helped to normalise experiences.

“Lots of new mums asking the same…When I was feeling lonely etc.”—Participant 6

Not only do new parents find a sense of reassurance when gaining advice from other new parents online, but it provides a sense of emotional support too. This can be critical for new parents, especially in situations where there is only one parent present. Sharing parenting techniques can lead to a wider knowledge base of best practise and reassure new parents that they are using the safest methods. Gleaning parenting advice online can also make new parents come to the realisation that they are not alone in their situation and many others are experiencing the same difficulties too.

Informational

Some new parents stated that their child was either, currently, or had previously experienced health issues. For this reason, new parents turned to the online platform to seek specific information which was relevant to said ailment or symptom. This allowed new parents to maintain and improve their knowledge, pertinent to their child’s health. Some parents searched for health information online due to symptoms which were typical to new born children, whilst others described how their child was experiencing symptoms and health issues which were atypical to new born children and were quite serious. For example, one participant discussed how the information online helped support them whilst at times also providing guidance.

“Our son has significant problems with his colon/bowel etc. and has had medication from 8 weeks old. With no real solution at the hospital and the problem getting worse we sometimes resort to the Internet for support/guidance”—Participant 81

Whilst some new parents search for symptoms which are somewhat pre-empted within new born babies, for example colic, this does not mean that these symptoms are any less concerning. It is salient to keep in mind that new parents are likely to have no familiarity with even the most innocuous symptoms, therefor, they can be perceived to be more severe than they actually are.

The qualitative data suggests that new parents whose children have a symptom or diagnosis which is atypical to being a new born baby, attempt to garner as much subject specific health information they possibly can in order to be, not only an informed parent, but also, an informed patient advocating for and choosing the best possible methods to minister to their child. Previous research has inferred that doctor-patient relationships are increasingly strengthened when a patient is equipped with all relevant tools needed to make an informed choice (23).

Anxiety

New parents who experienced anxiety in relation to their child’s wellbeing were prompted to use the online platform to seek health information. This was due to the fact that anxiety can cause a new parent to express undue concerns in relation to their child’s health and well-being, however, the online platform could also increase feelings of health anxiety as previous research has shown (5,24,25).

Increase

Becoming a new parent can cause exponential strain on cognition, leading to a higher prevalence of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression (26). This is especially salient when becoming a new parent. The post-partum period has been linked to a range of difficult emotional issues (27,28). Many new parents felt that becoming a parent had increased their health anxiety.

“It has increased my anxiety, left me vulnerable to worry about illnesses I’d never previously heard of”—Participant 2

“It makes it worse. I have become a slave to symptoms that could be caused by HA (Health Anxiety).”—Participant 3

New parents already experience an increase in anxiety in regards to their child’s health and wellbeing. Some individuals use the internet to excessively search health information, thus increasing both general and health anxiety. This phenomenon has been satirically termed “cyberchondria” (25). One particular concern is that, if health anxiety isn’t clinically diagnosed, that the onset could potentially be caused by the plethora of easily accessed, invalidated health information.

“It’s made my own health anxiety worse as I worry about not being there for my son as he grows up. Fearful of something happening to me that would prevent me from being there for my son.”—Participant 2

Postpartum state anxiety has been found to be an acute singularity, prevalent in new mothers yet widely unscreened for, essentially leading to higher levels of anxiety and mental health issues for a new mother, if not addressed (21,27,29).

Reduction

It appeared that, if the information and methods used tallied up to the new parent searching, that they would feel a level of reassurance within their own aptitude, essentially decreasing levels of anxiety.

“When it ties in with my belief that I’m doing a good enough job as a mother, that my baby will be OK and is not suffering or unhappy in any way.”—Participant 5

“It was reassuring to see that other mums experience similar challenges.”—Participant 55

Sometimes, new parents feel completely confident within their new parenting role and are assured that their methods, techniques and routines are the best for their child. Other new parents are not as confident and require certain levels of reassurance to reinforce this. Not only does the online platform allow new parents anonymity online, it also keeps self-doubt anonymous and allows new parents to explore various techniques and parenting methods without feeling as though they will be criticised for their inexperience and uncertainty (30).

Discussion

Overall, the results from this study reinforced previous literature (15) and adds to it. Anxiety specific to pregnancy ceases when gravidity comes to an end, as previous complications during pregnancy do not affect levels of health anxiety in new parents, since the new parent is no longer experiencing pregnancy and the child is now independently extant. Feelings of health anxiety then tend to be transferred from the mother (parent) to the child when one becomes a new parent.

New parents strive to expand their own knowledge base, in regards to typical and atypical symptomology, so that they are better equipped to monitor development, care for, and make decisions on behalf of, their child. The online platform was used as opposed to offline provisos due to inexperience, judgement and anonymity. Online health information seeking behaviour also has the probability of both increasing and decreasing levels of anxiety in new parents.

The results of this study also reinforced the positives of online health information seeking which have been reported in previous studies, such as receiving advice from likeminded individuals and normalisation of symptom. There were also negative aspects noted. New parents suggested that their levels of general and health anxiety were increased by using the online platform to acquire health information. This increase could cause a fixation when searching and further anxiety about health which in turn could be transferred to the child. It can be inferred that new parents are acutely aware of both the positive and negative aspects of online health information seeking but have difficulty in mediating the negative effects.

From this study, it is recommended that further research be carried out into relevant, efficacious interventional techniques that may relieve health anxiety within new parents as contemporary technology has become a pivotal aspect of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Bolton, the NCT and all who participated.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Rathbone AL, Prescott J. The Use of Mobile Apps and SMS Messaging as Physical and Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e295. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rathbone AL, Clarry L, Prescott J. Assessing the Efficacy of Mobile Health Apps Using the Basic Principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e399. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox S, Rainie L, Horrigan J, et al. The Online Health Care Revolution: How the Web Helps Americans Take Better Care of Themselves. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; November 2000. PIP_Health_Report. pdf. 2006. Available online: https://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/2000/PIP_Health_Report.pdf.pdf

- Gatto SL, Tak SH. Computer, Internet, and E-mail Use Among Older Adults: Benefits and Barriers. Educ Gerontol 2008;34:800-11. [Crossref]

- Prescott J, Mackie L, Rathbone AL. Predictors of health anxiety during pregnancy. mHealth 2018;4:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eastin MS, Guinsler NM. Worried and wired: effects of health anxiety on information-seeking and health care utilization behaviors. Cyberpsychol Behav 2006;9:494-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Health information seeking behavior. Qual Health Res 2007;17:1006-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bawden D, Robinson L. The dark side of information: overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science 2009;35:180-91. [Crossref]

- Lee HJ, Goetz AR, Turkel JE, et al. Computerized attention retraining for individuals with elevated health anxiety. Anxiety Stress Coping 2015;28:226-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barsky AJ. Assessing the New DSM-5 Diagnosis of Somatic Symptom Disorder. Psychosom Med 2016;78:2-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL. Hypochondriasis. An evaluation of the DSM-III criteria in medical outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:493-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcus DK, Gurley JR, Marchi MM, et al. Cognitive and perceptual variables in hypochondriasis and health anxiety: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:127-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warwick HM, Salkovskis PM. Hypochondriasis. Behav Res Ther 1990;28:105-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dworkin J, Connell J, Doty J. A literature review of parents’ online behavior. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 2013;7:2. [Crossref]

- Cotten SR, Gupta SS. Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1795-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prescott J, Mackie L. "You Sort of Go Down a Rabbit Hole...You're Just Going to Keep on Searching": A Qualitative Study of Searching Online for Pregnancy-Related Information During Pregnancy. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e194. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, Valentiner DP. The short health anxiety inventory: Psychometric properties and construct validity in a non-clinical sample. Cognit Ther Res 2007;31:871-83. [Crossref]

- Palaiologou I. editor. The early years foundation stage: Theory and practice. Sage, 2016.

- Alexander MJ, Higgins ET. Emotional trade-offs of becoming a parent: how social roles influence self-discrepancy effects. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993;65:1259-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gullone E. The development of normal fear: a century of research. Clin Psychol Rev 2000;20:429-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paul IM, Downs DS, Schaefer EW, et al. Postpartum anxiety and maternal-infant health outcomes. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duncan P. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. Hagan JF, Shaw JS. editors. 3rd edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007.

- Plantin L, Daneback K. Parenthood, information and support on the internet. A literature review of research on parents and professionals online. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach G, Jadad AR. Evidence-based patient choice and consumer health informatics in the Internet age. J Med Internet Res 2001;3:E19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muse K, McManus F, Leung C, et al. Cyberchondriasis: fact or fiction? A preliminary examination of the relationship between health anxiety and searching for health information on the Internet. J Anxiety Disord 2012;26:189-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Bussel JC, Spitz B, Demyttenaere K. Three self-report questionnaires of the early mother-to-infant bond: reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the MPAS, PBQ and MIBS. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010;13:373-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bina R, Harrington D. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Screening Tool for Postpartum Anxiety as Well? Findings from a Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Hebrew Version. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:904-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fallon V, Halford JCG, Bennett KM, et al. The Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale: development and preliminary validation. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016;19:1079-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Svensson J, Barclay L, Cooke M. The concerns and interests of expectant and new parents: assessing learning needs. J Perinat Educ 2006;15:18-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dutta-Bergman MJ. Health attitudes, health cognitions, and health behaviors among Internet health information seekers: population-based survey. J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Rathbone A, Prescott J. “I Feel Like A Neurotic Mother at Times”—a mixed methods study exploring online health information seeking behaviour in new parents. mHealth 2019;5:14.