Stick To It: pilot study results of an intervention using gamification to increase HIV screening among young men who have sex with men in California

Introduction

In the United States, men who have sex with men (MSM) experience a disproportionate burden of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Gay and bisexual men account for 70% of new HIV diagnoses (1), and if current rates continue, 1 in 6 MSM may be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime (2). Young MSM (YMSM) 13–24 years of age are at particularly high risk, accounting for 25% of new diagnoses among all MSM and overall, nearly 1 out of 5 new diagnoses in the U.S. (3). The epidemiologic data for other STIs is similarly concerning: the rate of primary and secondary syphilis increased 19% from 2014–2015 (4), with MSM comprising 60% of new cases, and the estimated rate of gonorrhea among MSM in six U.S. jurisdictions more than doubled from 2010 to 2015 (5). Homophobia, stigma, and discrimination may partially explain these worrying trends, along with prevention fatigue and complacency, especially among YMSM who did not experience the initial years of the HIV epidemic (6,7).

Although more tools than ever are available to prevent HIV, nearly all require a behavioral component to maximize effectiveness. For example, biomedical prevention strategies such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) require MSM to locate a provider, attend regular medical visits, adhere to the drug, be regularly screened for HIV/STIs and monitored for side effects, and use condoms or other methods to avoid STIs. While traditional behavioral approaches relying on information, education, and communication have had some success, a new field of behavioral science leverages people’s systematic biases and heuristics to positively change behavior (3-5). These approaches use tools from behavioral economics and psychology to influence behavior and include financial and in-kind incentives, social influence, commitments, and reminders. In addition, several studies have found that incorporating elements of games into programs, an approach known as gamification, can harness the motivational power of these same tools (e.g., incentives, commitments, reminders) in a context of fun (8,9).

Interventions using gamification are not games in the traditional sense. Instead, they are programs that include elements of games such as a reward system (e.g., points, badges, leaderboards), elements of chance and surprise, and/or a social component (e.g., connection, collaboration, and competition) (10). Ongoing and completed studies in the U.S. and elsewhere, including several intended for MSM, have demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of gamification for improving engagement in HIV prevention and care services (11-20). Programs incorporating gamification may be especially advantageous for YMSM given their engagement with technology, social media, and games. Indeed, a growing body of evidence suggests that the internet and social media are effective ways to share sexual health information with MSM, and YMSM in particular (21-29). It is therefore unsurprising that a generation of interventions drawing on gamification for YMSM is currently underway, including programs to reduce sexual risk behaviors and to improve antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence (13-16).

In order to test the potential of gamification for HIV prevention, we developed and piloted Stick To It, an HIV prevention intervention that incorporates elements of gamification to increase repeat HIV screening among YMSM (ages 18–26 years). We chose to focus our intervention on routinization of HIV screening as it is the gateway to HIV treatment, which can lead to reduced onward transmission (30), and also serves as a critical first step to accessing prevention strategies such as PrEP. Although CDC recommends annual HIV screening for MSM, clinicians can consider more frequent screening (e.g., every 3–6 months) for individual MSM at increased risk for acquiring HIV infection (31). More frequent screening is also supported by mathematical models and observational data indicating that smaller screening intervals could reduce transmission of STIs (32,33), are cost-effective (34), and will reduce undiagnosed HIV infection (35,36). Repeat HIV screening is also critical for men on PrEP (37), and to reduce undiagnosed HIV infections, especially as 52% of HIV infections among YMSM are undiagnosed (38). We hypothesized that an intervention using gamification that was developed through an iterative, human-centered and game-design process and leveraged existing technology would be acceptable to YMSM and could increase repeat HIV screening.

Methods

Study overview

Between October 2016 and June 2017, we conducted a pilot study at two sexual health clinics operated by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation in Hollywood and Oakland, California, USA. The mixed-methods evaluation strategy included data from surveys with participants, medical record reviews, intervention engagement data, and in-depth interviews with participants in order to determine intervention acceptability and its preliminary association with repeat HIV screening within 6 months. The study was pre-registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02946164) and the study protocol has been published (39).

Theoretical framework

Gamification, “the use of game-design elements in non-game contexts”, (8,9) is hypothesized to amplify the motivational power of financial and non-financial incentives in addition to other benefits. It is informed by Self-Determination Theory, which posits that external rewards can be internalized and generate lasting intrinsic motivation (defined as engaging in activities “because of the positive feelings resulting from the activities themselves”) if they are experienced in a context that satisfies three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (40). It is hypothesized that gamification has the potential to create such a context (8,40). In addition, gamification builds on economic and behavioral economic theory about how rewards motivate engagement in health behaviors (41-43).

Gamification interventions can be described by their ‘game mechanics’, the mechanisms that define how the intervention works, and their theme, the narrative or story that serves to connect game components (38). Our intention was to test the combination of simple game mechanics for YMSM (described below), with the expectation that these mechanics could also be customized to other target populations by modifying the theme.

Study population and recruitment

Young men were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (I) 18–26 years old, (II) were born as and/or self-identified as male, (III) reported male sexual partners at the time of enrollment (any kind of sexual contact(s) and/or relationship), and (IV) their zip code of residence surrounded one of the two study clinics so that study participants could realistically visit a study site. The inclusion criteria were intended to be as narrow as possible while permitting participation of higher-risk populations served by the participating clinics. For this reason, we increased the upper age limit from 24 to 26 years and permitted inclusion of self-identifying men (including transgender men) who met the other criteria.

Participants were recruited in-person at study sites by clinic and research staff as well as online via advertising on various social networking sites (e.g., Grindr, Facebook, Instagram, Craigslist) and through flyers placed in the community. Participants completed a web-based screening questionnaire, informed consent, and study registration online at the project website irrespective of how they were recruited; a clinic visit was not required.

Intervention description

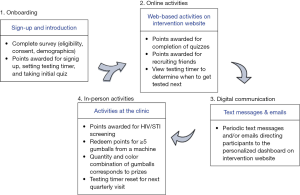

The intervention development process was influenced by game design and human-centered design and has been previously described in detail along with the proposed theory of change (39,44). In brief, a series of in-depth interviews with clinic staff and focus group discussions with YMSM solicited feedback about specific game elements followed by an iterative design process. Qualitative data collection was punctuated by design meetings with the project team to refine and finalize game elements, such as how to make use of points, whether to use a leaderboard and/or social component, the frequency of participant interaction, when or if to incorporate prizes, and how to make use of elements of chance. The final intervention consisted of four components (Figure 1): (I) recruitment, (II) online enrollment; (III) online activities, and (IV) ‘real-world’ activities that occurred at the clinic. Participants earned points through the online activities, which were then redeemed for a chance to win prizes during clinic visits. These components were connected through a gumball machine theme, selected by YMSM, and the program name of Stick To It, which also alluded to adoption of a regular HIV screening schedule.

The online enrollment process consisted of an eligibility survey, informed consent, a short survey to collect socio-demographic characteristics, and an introduction to the intervention and testing locations. This consisted of a brief, written tutorial, entering the date of last HIV screening which was used to set a digital countdown timer for the next recommended screening 3 months from the last test, and a five-question multiple choice quiz on a topic related to sexual health. Participants earned points for each step and all subsequent activities. Throughout the program, participants could also invite friends to join the intervention, and would earn points for their enrollment.

After enrollment, the intervention consisted of periodic quizzes that could be completed for points; every 3 weeks users were prompted via SMS and email to visit their dashboard on the intervention website to take a new quiz. Quizzes were short, whimsical, included questions that tested knowledge of sexual health information germane to YMSM, and were derived from the well-known “Ask Dr. K” online column (45). The quizzes had two primary goals: (I) display the approaching quarterly screening date on the countdown timer on the participant’s personalized dashboard, and (II) provide participants the opportunity to accumulate points, increasing their chance of winning prizes at the clinic, and thereby increasing motivation to seek HIV screening.

The final component of the intervention took place at the clinic where participants could be screened for HIV and STIs and/or redeem their points for a chance to win prizes. Prizes were determined via spins of a gumball machine, whereby points were used to ‘purchase’ spins and prizes were determined by the color combinations of gumballs, with an expected average prize cost of $5 per screening visit. Points could only be redeemed in clinic, a purposeful game mechanic intended to increase motivation to engage in regular sexual health services. After screening, the countdown timer was reset for the next quarterly screening date and the participant continued to receive new quizzes until the next visit or study end.

HIV and STI screening

At screening visits, clients were typically screened for HIV with the INSTITM HIV-1/2 antibody test, (bioLytical, Vancouver, CA, USA) and the Clearview® COMPLETE HIV 1/2 assay. Those with a non-reactive result were further screened with the Abbott ARCHITECT® Ag/Ab Combo (Abbott Architect i1000r, Abbott Park, IL, USA) test to detect acute and recent HIV infections. Anatomic site screening for STIs included oropharyngeal, rectal, and urethral for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis [Hologic APTIMA CT/NG assay (San Diego, CA, USA)], followed by a blood draw for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin screening with Treponema pallidum particle agglutination confirmation; Fujirebio, Japan). Clients with positive test results and recent sex partners were treated according to AHF clinical protocols in accordance with CDC and State of California STD treatment guidelines (46,47).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was intervention acceptability assessed with the following indicators of intervention engagement: completion of registration, completion of onboarding (setting the testing timer and completing the first quiz), completion of subsequent quizzes, recruitment of friends, redemption of points in the clinic, and HIV screening (during the study period). In addition, these data were supplemented with an ancillary qualitative study with a subset of participants. Note that changes in sexual behavior were pre-registered as a secondary outcome on clinicaltrials.org, but data on this outcome were not available in the medical record for most participants and is therefore not presented.

Among a subset of participants, we also assessed the intervention’s preliminary effectiveness on repeat HIV screening within 6 months, defined as the proportion of men in the intervention who received ≥2 HIV tests over 6 months of follow-up. This exploratory analysis was restricted to men who enrolled by January 30, 2017 (in order to have at least 6 months of follow-up) and those who were recruited in the clinics. This was because only men recruited in the clinic provided HIPAA authorization for review of medical records and were screened at baseline (tests within the previous 30 days of enrollment were counted as baseline tests).

Data collection

A brief online survey collected baseline socio-demographic characteristics. We collected detailed data on website analytics and participant engagement with the intervention, including completion of online activities, redemption of points, and HIV screening encounters. In the final 2 months of the pilot study, we conducted a qualitative study consisting of 15 in-depth interviews with Stick To It participants. We purposefully selected a diverse group of YMSM from different racial and ethnic groups and men who had different levels of engagement with the intervention after registration. Interviews were conducted in English by trained staff in a private room at study clinics or via phone and followed standard qualitative procedures (48,49). A semi-structured interview guide covered pre-determined issues but the interviewer was free to change the sequence and wording of questions to ensure that unexpected themes could emerge. Interviews were audio recorded, with participant’s consent, and later summarized according to intervention component (i.e., quizzes, peer recruitment). Interviews focused on whether the intervention was relevant, motivating, and culturally appropriate. Participants were compensated $50 and interviews continued until theme saturation (48).

To understand whether the intervention had preliminary effects on repeat HIV screening compared to the standard of care, medical records were reviewed for the subset of Stick To It participants who received services at the two participating clinics and who signed HIPPA authorization. We compared these data to a historical comparison group of 18–26 years old YMSM who received care at the same clinics during the 6 months preceding the intervention (January to September 2016) and who resided in the same eligible zip codes; intervention participants were excluded from this group. Although our analysis plan specified a comparison group of approximately the same size as the intervention group (39), to increase statistical power we included all 517 YMSM who met these criteria in the comparison group. In addition to being YMSM attending the same study clinics, the mean age (23 years) and sex of sex partners (83% men only) was the same in the historical comparison group and the Stick To It group.

Data analysis

We first describe the study population and intervention acceptability by examination of the quantitative indicators of intervention engagement. This included the proportion of all YMSM who completed registration, completed online enrollment (setting the testing timer and completing the first quiz), and redeemed points. We supplemented these data with insights about acceptability from the qualitative interviews, which were analyzed using a content analysis approach (50) and are co-presented with the quantitative data. One researcher coded the data from the interviews according to pre-determined codes such as the components of the intervention (e.g., quizzes, inviting friends, prizes, clinic-based activities) and the user experience (e.g., recruitment, SMS messages).

We hypothesized that intervention engagement would be related to enrollment procedures. For example, some similar mHealth programs require a baseline clinic visit (16,51). Although ideal from a research perspective, one might expect higher levels of engagement from participants who enroll in-person (a type of ‘commitment’ to the program) compared to those who are recruited and enrolled entirely online. In contrast, a fully online enrollment process may be ideal to reach those YMSM who are most disenfranchised, most concerned about stigma, and/or living in rural settings. For these reasons, we stratified most analyses by whether participants were recruited in the clinic or entirely online (note that those recruited in the clinic were typically also screened for HIV that day).

To determine the intervention’s preliminary effectiveness on repeat HIV screening within 6 months, we compared the frequency of repeat screening among the subset of participants recruited in the clinic to the historical comparison group. We assessed whether the proportion who received repeat screening was statistically different using a chi-squared test with alpha =0.05. We also expressed this comparison as an odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI. Similar to other small pilot studies of online sexual health interventions (51,52), this analysis was considered to be preliminary, as the pilot study was primary focused on acceptability and was not powered for an effectiveness analysis.

Protection of human subjects

The Committee for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Berkeley approved this study.

Results

During the study period, 629 people completed the online eligibility survey and 313 YMSM met the eligibility criteria. Of these, 166 (53%) registered for Stick To It, which included completing the online informed consent and baseline survey and creating an account on the Stick To It website. Of the 166 participants, 45 were recruited in the two participating clinics and 121 were recruited and enrolled online (primarily Grindr). Compared to the YMSM who were recruited online, YMSM recruited in the clinic were slightly older (mean age 23.4 vs. 22.8 years old), had higher levels of education (51.1% vs. 25.6% reported a college degree), were less likely to be students (44.4% vs. 52.1%), were more likely to be employed (82.2% vs. 61.2%), and had higher income (31.1% vs. 19.0% earned $30,000 or more annually; Table 1). Men recruited online were more likely to self-identify as Latino (49.6% vs. 26.7%), while men recruited in the clinic were slightly more likely to self-identify as Asian (22.2% vs. 10.7%) or African-American (8.9% vs. 3.3%).

Full table

Intervention acceptability and feasibility

Despite different levels of engagement, participants in the qualitative interviews provided a positive assessment of Stick To It, with several participants noting that they were motivated by the inclusion of games into the HIV/STI testing experience, which was otherwise stressful. One participant explained, “Trying to gamify the testing process makes it a little bit less stressful, a little bit less anxiety” (Oakland, Clinic, 25 years). Another participant noted, “It’s cool……I like the quizzes, I think the questions are pretty fun. I also like the fact that it encourages people to get tested…I think it’s a really good program” (Los Angeles, Online, 23 years).

Nevertheless, although most participants liked the program, some did not think that it was helpful for them individually because they reported that they were already regular testers and/or did not need additional encouragement. Likewise, participants ranged in how they perceived the prizes, from high levels of enthusiasm to interest only in high-value prizes (which were perceived by some as too difficult to win). For example, one participant explained, “In general I thought it was well intentioned, but I did not really see any benefit. And there’s two reasons. One is the prizes…they were not something I wanted. And the second [reason] was I get tested for STDs without any encouragement, it’s just something you do (Los Angeles, Online, 25 years).” In this way, participants saw value in the program in general but differed about whether it was individually motivating.

Enrollment

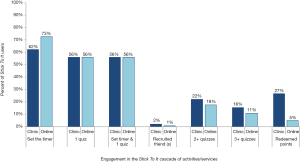

Immediately after registration, participants were prompted to set the testing countdown timer and to answer the first quiz. Overall, 56% of participants completed both enrollment activities, although 73% of men who were recruited online set the testing countdown timer compared to 62% of men recruited through the clinics (Figure 2). Interviews suggested several explanations for some participants’ inactivity after registration. For some participants, the program benefits were unclear, with one participant explaining, “When I originally joined the program… I just thought it was an online only resource and found out that it’s more than that” (Oakland, Online, 25 years). Men recruited online in particular found that the website offered insufficient guidance on the next steps following enrollment. One participant noted, “I remember kind of waiting and wondering when are they gonna try to get me to go, which clinic are they gonna try to get me to go to, how can I verify that I went if I did go get checked out?” (Los Angeles, Online, 22 years). Other participants indicated that the prizes were insufficiently described during the enrollment process and they didn’t know what they were “playing for” until they received the first program SMS or email.

Post-enrollment online activities

Online activities included completion of periodic quizzes and recruiting friends in exchange for points. Of the 164 participants who registered and who had 6 months of follow-up, 31 (19%) completed ≥1 online activity in the 6 months after enrollment. Men recruited through the clinic completed more quizzes: 22% of participants recruited in the clinic answered ≥2 quizzes (one additional quiz following enrollment) and 16% answered ≥3 quizzes. In comparison, of the men recruited online, 18% answered ≥2 quizzes and 11% answered ≥3 quizzes. Men recruited in clinics were also active on the website longer than men recruited online (days between registration to last login =19.2 vs. 12.9 days) and checked the website more often (mean number of logins: 3.1 vs. 2.1).

In qualitative interviews, most participants reported that they enjoyed the quizzes; some participants continued to answer quizzes even if they did not plan to redeem the points. However, engagement was negatively impacted if participants perceived that the program wasn’t strongly connected to or visible at the clinic, as one participant explained, “I took one or two quizzes. But after I got tested and no one mentioned the program, I stopped doing the quizzes.” (Oakland, Clinic, 21 years).

Only two participants successfully recruited a friend who signed up. Participants provided several reasons for not recruiting friends, including the difficulty in discussing HIV testing with friends in general, apprehension that their invitation might imply that they think their friends are promiscuous, and the perception that friends would not want to participate in the program because they do not think they are at risk for HIV, because they go to other clinics than the two participating clinics, or because they do not live in the vicinity of the participating clinics. For example, one participant explained:

“Would I invite anybody? If it were anonymous, yes I might. But if they had to know that I sent them the invitation, I would not… I’m not gonna say slut shaming, but by me inviting one of my friends to remind him or her to go get tested, I’m sort of saying ‘I know you have the need to go get tested,’ which a lot of times people interpret as ‘really, do I sleep around that much, do you think that about me?’”(Los Angeles, Online, 25 years)

In this way, there was low demand to recruit friends for the program.

Clinic activities

Overall, 27% and 5% of those recruited in the clinic and online, respectively, redeemed their points in the clinic for a prize. Some participants visited clinics during the study period but reported that they were not planning on redeeming points in order to increase their chance for higher value prizes at subsequent visits. In addition, although men had to reside near the two AHF clinics to be eligible, qualitative data revealed that for many men who signed up online, the clinic was perceived as too far away, inconvenient, or too busy. One man summarized, “If you want guys to be a part of this program, they should be able to get tested at any clinic” (Oakland, Clinic, 25 years).

Preliminary effectiveness on repeat HIV screening

The analysis of repeat HIV testing during the study period was assessed among 31 YMSM recruited in the clinic who also provided consent and HIPAA authorization for review of medical records. During the study period, 15 (48%) received two or more HIV tests compared to 157 (30%) of a historical comparison group of 517 YMSM who lived in the same zip codes and who received care at the same clinics before the intervention (OR =2.15, 95% CI: 1.03–4.47, P=0.04).

Discussion

We conducted a pilot evaluation of an intervention incorporating gamification to increase repeat HIV screening among YMSM in California. Given that YMSM remain disproportionally impacted by HIV and STIs, novel approaches that bolster proven HIV prevention strategies, such as screening, treatment, and linkage to PrEP and HIV treatment, may serve an important public health function (3). We found that the Stick To It intervention was acceptable to study participants, although engagement was modest such that only about 1 of every 5 YMSM completed any activities after registration. We learned valuable insights about desirable intervention features which might increase effectiveness, such as the inclusion of multiple clinics in the same area, as well as undesirable features, such as the option to recruit peers. Promisingly, among the subset of participants recruited in the clinic, repeat HIV screening was higher than in a comparison group of similar YMSM attending the same clinic in the year prior.

The success of online HIV/STI prevention programs is strongly linked to participant engagement. We observed only moderate levels of engagement with Stick To It, which was intentionally designed for online enrollment (no clinic visit), without financial incentives to encourage use, and without additional research visits. On the positive side, despite a somewhat time-consuming sign-up process due to the requirement of online informed consent, 56% of those who registered completed onboarding. Notably, among the subset of YMSM recruited entirely online with no contact with the study team, 73% set the testing countdown timer, which activates the reminder system and is a type of “commitment device”, a strategy demonstrated to motivate behavior change (53-55). Furthermore, many YMSM successfully made the transition between desired online ‘digital actions’, such as setting the timer and completing quizzes. However, 30 days after enrollment, only about 10% of Stick To It users were completing quizzes and the linkage between online and real-world activities was relatively low, with only 11% of those who registered visiting a study clinic during the pilot study.

This level of engagement is similar to other primarily online health interventions such as Just/Us (29), the sexual health Facebook intervention for young adults, SOLVE (24), an online game to reduce shame among MSM, and the Keep It Up! (18) online HIV prevention intervention for young adults. In Just/Us, retention was 51% at 6 months and only 10% were “loyal” visitors (29). In the SOLVE game, only 444 of 1,284 (35%) MSM randomized to the intervention had a minimum level of engagement at 3 months (i.e., baseline survey and game registration) to be included in the per-protocol analysis (24). In Keep It Up!’s community-based evaluation, only 343 of 755 (45%) people completed the intervention; of these, 42% were lost to follow-up at 3 months (18). Thus, the level of engagement in Stick To It is not atypical from other online mHealth programs focusing on sexual health, all of which are characterized by a pattern of early attrition (56). This phenomenon is also observed in industry: data from the private sector suggests that 23% of mobile users abandon an app after one use (57) and the average app loses 77% of its daily active users within the first 3 days after install and loses 90% of users within 30 days (58).

A surprising finding was that men recruited entirely online—without any direct contact with the study team or health clinic—had similar levels of engagement for some indicators as men recruited in the study clinics. These men received no incentive for signing up for the program or completing digital actions yet 18% completed two or more quizzes during the program and 5% redeemed points. This is encouraging and demonstrates the potential of this approach. Although men recruited online had predictably much lower engagement in the clinic-based activities (e.g., redemption of points or screening at one of the two study clinics), potentially due to the inclusion of only two clinics, the addition of multiple clinics within a defined catchment area and/or home delivery of HIV/STI kits for self-collected specimens that can be returned by mail could expand the reach of these programs to a wider network of YMSM, including those who are not actively engaged in care and/or those in rural areas (59). Furthermore, these data indicate that investment in a fun and engaging online program could modestly increase engagement in HIV screening with minimal effort after the initial development phase.

This pilot study has important limitations. Like other pilot studies of mHealth interventions (51,52), this was a small study with the goal to assess the acceptability of a program using theoretically-based game-based elements for HIV prevention among YMSM. However, the study was conducted in only two clinics in California; a larger study incorporating these insights is now needed. Consistent with prior studies (60), acceptability was primarily based on behavior (i.e., engagement) and self-reported experiences; more rigorous acceptability measures like satisfaction measures and attitudinal measures were not used. Qualitative interviews were restricted to YMSM who, at a minimum, completed registration. In addition, we were only able to assess the primary outcome of repeat testing among men recruited in the clinic and who signed HIPPA authorization (required by IRB to be completed in person) for review of medical records. Thus, although the inclusion of men recruited online was valuable in terms of understanding participant engagement, we could not review their medical records unless they visited a study clinic. Baseline data indicate that men recruited in the clinic vs. online are different; therefore, alternative evaluation strategies will be needed in future studies for men recruited online, including alternative options to comply with HIPAA regulations and IRB requirements. In addition, we could only assess medical records at participating study clinics; a future study will explore how to verify testing behavior at multiple clinics within a defined geographic area. Additional research is also needed to apply these tools to maximally benefit specific vulnerable populations such as transgender men and women.

Lastly, it is unlikely that stand-alone gamification interventions could replace other behavioral interventions to increase demand for HIV and STI prevention. Accordingly, we combined known behavior-change mechanisms such as reminders, commitments, and incentives along with standard health services using a game-based approach including a theme. A potential limitation of this approach is that we cannot disentangle the effects of various intervention components. However, the combined approach is likely what has most relevance for future programs, especially if other strategies like home-based self-testing and PrEP are added to the program (61).

Behavior change is about finding the right tools to motivate different kinds of people (53). Gamification interventions may resonate particularly well with young people, who are extremely comfortable with games and technology (11). Our pilot study suggests that this approach may hold promise as a motivational strategy to improve the sexual health of some YMSM, especially if lessons from this pilot are addressed and programs are coupled with implementation science research to optimize integration of online activities with real-world health services.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the clinic staff and clients who participated in the study and Jamie Murkey, Dr. Daniel Acland, Dr. Sean Young, Sagar Amin, Branden Barger, and Dale Gluth for participation in the intervention design process. The authors also recognize the valuable guidance from Gabe Zichermann about gamification mechanics and program design and the Stick To It Community Advisory Board for helpful feedback throughout the study.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Award Number R34MH106359 to SI McCoy). The funders were not involved in the review and approval of the manuscript for publication.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015. In: Volume 27. Atlanta, GA. November 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf

- Hess K, Hu X, Lansky A, et al., editors. Estimating the Lifetime Risk of a Diagnosis of HIV Infection in the United States. Boston: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016. In: Volume 28. Atlanta, GA. November 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2015. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016.

- Stenger MR, Pathela P, Anschuetz G, et al. Increases in the Rate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Among Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men-Findings From the Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance Network 2010-2015. Sex Transm Dis 2017;44:393-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacKellar DA, Hou SI, Whalen CC, et al. HIV/AIDS complacency and HIV infection among young men who have sex with men, and the race-specific influence of underlying HAART beliefs. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:755-63. [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. 2014. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors/pdf/hiv_factsheet_ymsm.pdf

- Deterding S. Meaningful Play: Getting Gamification Right. Google Tech Talk, 2011.

- Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R, et al., editors. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. Tampere, Finland: Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, 2011.

- McGonigal J. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin, 2011.

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Bauermeister JA, et al. The future of digital games for HIV prevention and care. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017;12:501-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J, et al. A systematic review of recent smartphone, Internet and Web 2.0 interventions to address the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:173-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeGrand S, Muessig KE, Platt A, et al. Epic Allies, a Gamified Mobile Phone App to Improve Engagement in Care, Antiretroviral Uptake, and Adherence Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men and Young Transgender Women Who Have Sex With Men: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeGrand S, Muessig KE, McNulty T, et al. Epic Allies: Development of a Gaming App to Improve Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Among Young HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men. JMIR Serious Games 2016;4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, LeGrand S, Simmons R, et al., editors. healthMpowerment: effects of a mobile phone-optimized, Internet-based intervention on condomless anal intercourse among young black men who have sex with men and transgender women. Paris: 9th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science, 2017.

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Pike EC, et al. HealthMpowerment.org: Building Community Through a Mobile-Optimized, Online Health Promotion Intervention. Health Educ Behav 2015;42:493-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mustanski B, Madkins K, Greene GJ, et al. Internet-Based HIV Prevention With At-Home Sexually Transmitted Infection Testing for Young Men Having Sex With Men: Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Keep It Up! 2.0. JMIR Res Protoc 2017;6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greene GJ, Madkins K, Andrews K, et al. Implementation and Evaluation of the Keep It Up! Online HIV Prevention Intervention in a Community-Based Setting. AIDS Educ Prev 2016;28:231-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Knudtson K, Muessig KE, et al., editors. AllyQuest: engaging HIV+ young MSM in care and improving adherence through a social networking and gamified smartphone application (App). Paris: 9th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science, 2017.

- Whiteley L, Brown L, Lally M, et al. A Mobile Gaming Intervention to Increase Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment for Youth Living With HIV: Development Guided by the Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills Model. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Monahan C, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention program for diverse young men who have sex with men: the keep it up! intervention. AIDS Behav 2013;17:2999-3012. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosser BR, Wilkerson JM, Smolenski DJ, et al. The future of Internet-based HIV prevention: a report on key findings from the Men's INTernet (MINTS-I, II) Sex Studies. AIDS Behav 2011;15 Suppl 1:S91-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Margolis AD, Joseph H, Hirshfield S, et al. Anal Intercourse Without Condoms Among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men Recruited From a Sexual Networking Web site, United States. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41:749-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christensen JL, Miller LC, Appleby PR, et al. Reducing shame in a game that predicts HIV risk reduction for young adult MSM: a randomized trial delivered nationally over the Web. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18716. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel V, Lounsbury D, Berrios A, et al., editors. Developing a Peer-Led Social Media Based HIV Testing Intervention with YMSM of Color - a feasibility study. San Francisco, CA: youth + tech + health Conference, 2014.

- Jones V, Whitlock M, editors. What's Going on Online WIth Hard to Reach Population? Social Media Use Among Black Gay Men. San Francisco, CA: youth + tech + health Conference, 2014.

- Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Joseph H, et al. An online randomized controlled trial evaluating HIV prevention digital media interventions for men who have sex with men. PLoS One 2012;7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bull SS, Breslin LT, Wright EE, et al. Case study: An ethics case study of HIV prevention research on Facebook: the Just/Us study. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:1082-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bull SS, Levine DK, Black SR, et al. Social media-delivered sexual health intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:467-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Irwin K, et al. Recommendations for HIV Screening of Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:830-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fairley CK, Law M, Chen MY. Eradicating syphilis, hepatitis C and HIV in MSM through frequent testing strategies. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014;27:56-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klausner JD. Frequency of syphilis testing in HIV-infected patients: more and more often. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:86-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson A, Sansom S, Farnham P, editors. Cost-effectiveness of more frequent HIV screening of men who have sex with men in the United States. Washington, DC: 19th International AIDS Conference, 2012.

- Burns DN, DeGruttola V, Pilcher CD, et al. Toward an endgame: finding and engaging people unaware of their HIV-1 infection in treatment and prevention. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014;30:217-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raymond HF, Chen YH, Ick T, et al. A new trend in the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004-2011. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62:584-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Underhill K, Operario D, Skeer M, et al. Packaging PrEP to Prevent HIV: An Integrated Framework to Plan for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation in Clinical Practice. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh S, Song R, Johnson AS, et al. HIV Incidence, HIV Prevalence, and Undiagnosed HIV Infections in Men Who Have Sex With Men, United States. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:685-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mejia CM, Acland D, Buzdugan R, et al. An Intervention Using Gamification to Increase Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Sexually Transmitted Infection Screening Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men in California: Rationale and Design of Stick To It. JMIR Res Protoc 2017;6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deci E, Ryan RM. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can Psychol 2008;49:14-23. [Crossref]

- O'Donoghue T, Rabin M. Doing it now or Later. Am Econ Rev 1999;89:103-24. [Crossref]

- Loewenstein G, Brennan T, Volpp KG. Asymmetric paternalism to improve health behaviors. JAMA 2007;298:2415-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 1974;185:1124-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- IDEO.org. The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design. Canada, 2015. Available online: http://www.designkit.org/resources/1

- San Francisco City Clinic. Ask Dr. K. San Francisco, CA. Available online: http://www.sfcityclinic.org/drk/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: Sex Transm Dis Treatment Guidelines, 2010.

- California Department of Health Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screen, Test, Diagnose, & Prevent. A Clinician's Resource for STDs, 2007.

- Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, 1994.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hightow-Weidman L, Muessig K, Knudtson K, et al. A Gamified Smartphone App to Support Engagement in Care and Medication Adherence for HIV-Positive Young Men Who Have Sex With Men (AllyQuest): Development and Pilot Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2018;4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lykens J, Silva C, Klausner JD, et al., editors. PrEPTECH: Bringing PrEP Access and Adherence Online. Atlanta, GA: American Public Health Association, 2017.

- Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, et al. Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. J Econ Psychol 2012;33:264-77. [Crossref]

- Williams BR, Bezner J, Chesbro SB, et al. The Effect of a Behavioral Contract on Adherence to a Walking Program in Postmenopausal African American Women. Top Geriatr Rehabil 2005;21:332-42. [Crossref]

- Rogers T, Milkman KL, Volpp KG. Commitment devices: using initiatives to change behavior. JAMA 2014;311:2065-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res 2005;7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Connell C. 23% of Users Abandon an App After One Use. Localytics, 2016. Available online: http://info.localytics.com/blog/23-of-users-abandon-an-app-after-one-use

- Chen A. New data shows losing 80% of mobile users is normal, and why the best apps do better. Available online: http://andrewchen.co/new-data-shows-why-losing-80-of-your-mobile-users-is-normal-and-that-the-best-apps-do-much-better/?utm_content=buffere4fa2&utm_medium=twitter.com&utm_source=social&utm_campaign=buffer

- Salow KR, Cohen AC, Bristow CC, et al. Comparing mail-in self-collected specimens sent via United States Postal Service versus clinic-collected specimens for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in extra-genital sites. PLoS One 2017;12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Youth Tech Health. PrEPTECH. Available online: https://www.preptechyth.org/#/home

Cite this article as: McCoy SI, Buzdugan R, Grimball R, Natoli L, Mejia CM, Klausner JD, McGrath MR. Stick To It: pilot study results of an intervention using gamification to increase HIV screening among young men who have sex with men in California. mHealth 2018;4:40.