Telehealth adoption for substance use and mental health disorders in Minnesota and North Dakota: a quasi-experimental study

Highlight box

Key findings

• Although North Dakota (ND) experienced a steady, gradual increase in telehealth usage before the pandemic, MN has been more successful in sustaining telehealth usage during and after the pandemic.

What is known and what is new?

• Transition to telehealth needs various resources including technology and financial investments.

• The success and sustainability of telehealth implementation depends on factors such as resources access, population diversity, cultural considerations, and patient age.

• Considering the challenges faced by states like ND face, the effective implementation of telehealth requires a systemic and holistic approach.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Policymakers should focus on investing in broadband infrastructure, creating favorable reimbursement policies, supporting ongoing training programs, encouraging collaboration among stakeholders, and establishing monitoring systems for continuous evaluation.

• Healthcare providers should inform patients about the benefits of telehealth, engage with diverse populations, and assess the adequacy of treatment based on individual patient needs.

Introduction

Telehealth, which involves utilizing telecommunication technologies for remote clinical healthcare, has long been recognized as a feasible, acceptable, and cost-effective alternative to those of traditional in-person therapy, particularly for cognitive and behavioral therapy (1,2). During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency, the flexibility and convenience of telehealth became significant assets, especially for serving people in rural communities, facilitating its expansion across many states in the country (3,4).

Several studies have showed that telehealth increases patient satisfaction (5,6), reduce travel time (7), enhance communication with providers (8), and increases access to care (9). Providers also benefit from fewer missed appointments, shorter waiting times, and improved care quality (10-12). Despite these proven positive outcomes, the usage of telemedicine has decreased post-pandemic. According to the National Health Statistics Reports (13), telehealth usage among adults decreased by 7% over the past year, with more pronounced declines in small cities and rural areas (14).

This research aims to analyze telehealth usage for behavioral health services in North Dakota (ND) and Minnesota (MN). These states provide a valuable comparison due to their differing demographics and healthcare infrastructure. ND has a higher rural population (42.7%) compared to MN (16%), posing unique challenges for telehealth adoption (15). Additionally, ND has a higher percentage of residents aged 65 years and older (21%) (16) than MN (17%) (17), making telehealth adoption more challenging due to technology unfamiliarity among older adults. Cultural factors, including the needs of migrant communities and Native Americans, also influence telehealth implementation in these states.

Transitioning from in-person to virtual methods requires various resources, including technology and financial investment. Rural communities often face more significant challenges in this transition. Therefore, understanding the trends and patterns of telehealth usage in ND and MN can provide insights for developing targeted strategies to enhance telehealth adoption and sustainability in different community settings.

This quasi-experimental study aimed to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth service utilization for substance use disorders (SUDs) and mental health care (MHC) among Medicaid beneficiaries in ND and MN. By analyzing Medicaid telehealth claims data from 2018 to 2022, this research provides insights for policy recommendations and strategic planning.

Methods

We conducted a quasi-experimental study to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth service utilization for SUDs and MHC in ND and MN. Segmented regression analysis (SRA) of interrupted time series (ITS) data was employed from January 2018 to December 2022.

Data source and selection

We used recently released Medicaid telehealth claims data from the Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) population database. The database comprised monthly counts and rates (per 1,000 beneficiaries) of behavioral health services across states. The dataset includes key variables such as the number of telehealth claims for SUD and MHC, stratified by state (ND and MN), the rate of telehealth utilization per 1,000 beneficiaries, and a time variable representing each month from January 2018 to December 2022.

Data quality using criteria from the Data Quality (DQ) Atlas, which taken into account factors such as enrollment totals and claims volumes. Data that do not meet these quality standards, including records with incomplete or inconsistent records, were excluded from the analysis. For confidentiality, any group data representing fewer than 11 beneficiaries were suppressed and denoted as “DS”. The inclusion of comprehensive monthly data over a five-year (2018–2022) spans enabled a robust assessment of trends in telehealth utilization, allowing us to capture both immediate and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth services for SUDs and MHC. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

ICD coding and data exclusion criteria

According to Medicaid methodology, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) coding was employed to ensure data accuracy. The percentage of records in each claims file containing a valid ICD-10 diagnosis code in the primary diagnosis code field (DGNS_1_CD) was assessed to ascertain the reliability of the dataset for analyzing telehealth service utilization patterns (18). This meticulous approach enhanced the reliability and validity of the analysis.

SRA

SRA is an ideal statistical method for evaluating the effect of interventions over time. By analyzing time-series data, it precisely identifies and measures shifts in service use levels and trends before and after significant events.

Rationale

Segmented regression models and detects changes in telehealth utilization pre- and post-pandemic, adjusting for underlying trends over time. This method helps to isolate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from other temporal trends that might affect telehealth usage.

Explanation of interaction terms

Interaction terms in the segmental regression model capture changes in the slope of the time series before and after the intervention (COVID-19 pandemic onset). These terms help understand both immediate effects (level changes) and trend changes (slope changes) post-intervention.

Key components of the model included:

- Time: a continuous variable indicating the month count from the beginning of the study period.

- Intervention (COVID-19 pandemic onset): a binary variable differentiating between pre- [0] and post- [1] pandemic phases.

- Time after intervention: an interaction term to model that post-intervention trend.

The statistical model was represented as:

Where Yt signifies the telehealth service count or rate at time t, with β coefficients represents the model parameters, and denoting the error term.

Statistical analysis

Segmented regression models were independently fitted for SUDs and MHC telehealth utilization in ND and MN, allowing a nuanced analysis of specific trends and changes in each state and condition. Changes in level and trend for telehealth service utilization were calculated and presented with 95% confidence intervals to ascertain significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using Python, specifically the ‘statsmodels’ package for regression modeling, with ‘matplotlib’ and ‘pandas’ aiding in data manipulation and graphical representation. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

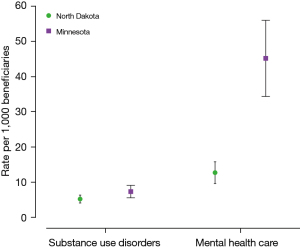

During the study period from 2018 to 2022, there were 580,186 telehealth claims for SUDs (MN: 545,676; ND: 34,510) and 3.4 million for MHC (MN: 3.3 million; ND: 85,391). The mean telehealth utilization rate for SUDs was 5.2 per 1,000 beneficiaries in ND and 7.3 per 1,000 beneficiaries in MN. For MHC, the mean telehealth utilization rate was 12.6 per 1,000 beneficiaries in ND and 45.2 per 1,000 beneficiaries in MN (Table 1).

Table 1

| Year | North Dakota | Minnesota | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telehealth | SUD | MHC | Telehealth | SUD | MHC | ||||||||||||

| Cases | Rate per 1,000 beneficiaries | Cases | Rate per 1,000 beneficiaries | Cases | Rate per 1,000 beneficiaries | Cases | Rate per 1,000 beneficiaries | Cases | Rate per 1,000 beneficiaries | Cases | Rate per 1,000 beneficiaries | ||||||

| 2018 | 10,276 | 4.8 | 1,368 | 1.2 | 1,246 | 1.1 | 65,455 | 8.8 | 4,781 | 0.4 | 19,697 | 1.5 | |||||

| 2019 | 11,162 | 6.0 | 1,784 | 1.6 | 1,938 | 1.7 | 77,267 | 9.9 | 5,065 | 0.4 | 24,299 | 1.9 | |||||

| 2020 | 105,454 | 202.8 | 13,564 | 11.1 | 33,016 | 26.9 | 2,792,825 | 86.4 | 180,964 | 13.1 | 1,148,232 | 83.4 | |||||

| 2021 | 82,545 | 180.7 | 9,643 | 6.8 | 27,652 | 19.7 | 2,748,647 | 58.7 | 212,888 | 14.0 | 1,272,329 | 83.6 | |||||

| 2022 | 67,654 | 113.9 | 8,151 | 5.3 | 21,539 | 14.0 | 1,862,989 | 43.8 | 141,978 | 8.7 | 906,831 | 55.5 | |||||

SUD, substance use disorders; MHC, mental health care.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

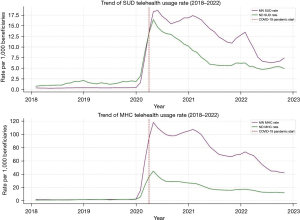

The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant increases in Medicaid telehealth use in both states. In ND, telehealth utilization rates for SUDs increased by 22.7 per 1,000 beneficiaries and for MHC by 59.8 per 1,000 beneficiaries. In MN, the increases were 30 per 1,000 beneficiaries for SUDs and 185.5 per 1,000 beneficiaries for MHC. ND experienced a smaller initial increase but more gradual declines over time, with SUDs showing a monthly decline of 0.42 per 1,000 beneficiaries and MHC showing a decline of 1.03 per 1,000 beneficiaries per month. In contrast, MN experienced larger initial increases followed by steeper declines, with SUDs showing a monthly decline of 0.43 per 1,000 beneficiaries and MHC showing a decline of 2.78 per 1,000 beneficiaries per month (Figure 1).

Annual telehealth service utilization

Examining the annual breakdown of telehealth service utilization, ND telehealth cases for SUDs escalated from 1,368 in 2018 to 8,151 in 2022, peaking at 13,564 in 2020. Similarly, MHC-related telehealth cases in ND rose from 1,246 in 2018 to 21,539 in 2022, with the highest at 33,016 in 2020. Meanwhile, MN experienced a more dramatic increase; SUD-related cases rose from 4,781 in 2018 to 141,978 in 2022, peaking at 180,964 in 2020. For MHC, MN saw an increase from 19,697 cases in 2018 to 906,831 in 2022, with the highest peak of 1,148,232 cases in 2020.

Comparing the telehealth utilization before and after the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted a dramatic increase. ND witnessed increases from 1.57 to 8.14 per 1,000 beneficiaries for SUDs and from 1.86 to 21.51 per 1,000 beneficiaries for MHC. In MN, the mean telehealth utilization rate for SUDs increased from 0.51 to 12.86 per 1,000 beneficiaries and for MHC from 3.19 to 79.47 per 1,000 beneficiaries. This significant change underscores the substantial increase in telehealth service usage for both SUDs and MHC in ND and MN.

Rate of telehealth utilization per 1,000 beneficiaries

The rate of telehealth utilization per 1,000 beneficiaries also showed a significant increase. In ND, the rate for SUDs increased from 1.2 per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2018 to 5.3 per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2022, while the MHC rates grew from 1.1 to 14.0 per 1,000 beneficiaries during the same period. In contrast, MN saw a large increase, with SUD rates escalating from 0.4 per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2018 to 8.7 per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2022, and MHC rates jumping from 1.5 to 55.5 per 1,000 beneficiaries (Figure 2).

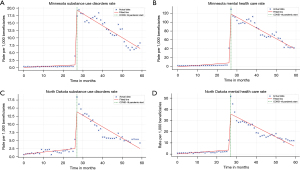

Trends in Medicaid telehealth usage in MN and ND

The SRA of ITS data revealed distinct patterns in the utilization of telehealth services for SUDs and MHCs between ND and MN during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 3). In MN, the impact of the pandemic on telehealth utilization for both SUDs and MHCs was markedly pronounced. The immediate level change for SUD services showed a surge of approximately 32,741 (95% CI: 29,410 to 36,072) services, with a subsequent decline in the monthly trend by about −423 (95% CI: −538 to −307) services. The rate per 1,000 beneficiaries for SUDs initially increased by 30 (95% CI: 28 to 32), followed by a monthly decrease of −0.43 (95% CI: −0.51 to −0.35). For MHCs, the initial spike was even more substantial, with an increase of around 201,511 (95% CI: 184,270 to 218,751) services, and a post-pandemic monthly reduction of −2,714 (95% CI: −3,310 to −2,117) services. The rate per 1,000 beneficiaries for MHCs saw a significant initial rise of 185.5 (95% CI: 172 to 199), with a monthly decrease of −2.78 (95% CI: −3.25 to −2.30) thereafter.

In contrast, ND exhibited a more moderated response to the pandemic in terms of telehealth utilization. The immediate increase for SUD services was about 2,172 (95% CI: 1,935 to 2,408) services, with a modest monthly decrease of −37 (95% CI: −45 to −28) services. The rate per 1,000 beneficiaries for SUDs in ND increased by 22.7 (95% CI: 20.1 to 25.3) initially, and then decreased by −0.42 (95% CI: −0.51 to −0.33) monthly. For MHCs, the immediate level change showed an increase of 5,720 (95% CI: 5,155 to 6,284) services, with a monthly trend decrease of −89 (95% CI: −108 to −69) services. The rate per 1,000 beneficiaries for MHCs increased by 59.8 (95% CI: 53.3 to 66.2) at the onset of the pandemic, with a subsequent monthly decline of −1.03 (95% CI: −1.25 to −0.80).

Discussion

This study analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth service utilization for SUDs and MHC among the Medicaid population in ND and MN. Our findings revealed that telehealth usage for SUDs in ND was three times higher than in MN before the pandemic. For MHC, both states had similar rates per 1,000 beneficiaries before the pandemic. However, trends indicate that MN had a mental telehealth rate of 83.4 per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2020, which remained stable until 2022, when it dropped to 55.5 per 1,000 beneficiaries. Meanwhile, the rate in 2020 for ND was only 26.9 per 1,000 beneficiaries, and it has dropped by 6 points each year since then.

The immediate surge in telehealth utilization observed in both states underscores the critical role telehealth played in maintaining access to behavioral health services during the pandemic. MN experienced a more pronounced initial increase followed by a steeper decline, suggesting rapid adoption but challenges in post-pandemic sustainability. In contrast, ND exhibited a more gradual but sustained increase and decrease in telehealth utilization, indicating a potentially more sustainable model of telehealth service delivery.

The significant differences in telehealth utilization rates between MN and ND, particularly for MHC, can be attributed to factors such as resource access, population diversity, cultural factors, and patient age. Transitioning from in-person to telehealth requires various resources, including technology and financial investment (2). This transition is usually more difficult for rural communities where access to and proficient use of virtual methods are limited (19). ND, with its higher rural population (42.7%), faces greater challenges compared to MN, where 84% of the population lives in urban areas.

Patient age play critical role in telehealth adoption. ND has a higher percentage of residents aged 65 years and older (21.3%) compared to MN (17%), making telehealth adoption more challenging due to older adults’ unfamiliarity with technology. Additionally, findings of previous studies show that adults living in the Midwest and South of the United States are less likely to use telemedicine than adults living in Northeast and West (16,17,20,21). Another cultural factor to consider is the needs and practices of migrants and Native Americans, also influence telehealth implementation in these states. Telehealth implementation must take these needs and practices into account, as well as affordability, which may require a change in funding models (22,23).

Ensuring the suitability of telehealth therapy for patients is essential. For patients with severe mental illnesses, such as active psychosis or suicidality, or in situations where confidentiality is paramount (e.g., domestic violence or child maltreatment), telehealth may not be the best option (24). Overall, MN has been more successful in maintaining telehealth usage during and after the pandemic compared to ND. The challenges faced by ND stem from various factors, which may explain why MN is in a better position. Therefore, given the specific circumstances in ND, the implementation and sustainability of telehealth in the state require a systemic and holistic approach.

The more sustainable telehealth trends observed in ND provide valuable insights for policymakers and healthcare providers aiming to enhance the adoption and long-term sustainability of telehealth services. Several factors could contribute to these trends, including effective telehealth infrastructure, targeted outreach programs, and robust support systems for both patients and providers. The gradual but sustained increase in telehealth utilization in ND suggests that a phased approach to telehealth implementation, combined with continuous support and evaluation, can lead to more sustainable outcomes.

Enhancing telehealth infrastructure by investing in reliable broadband internet access, particularly in rural and underserved areas, can significantly improve accessibility and reliability of telehealth services (25). Comprehensive training for healthcare providers on telehealth technologies and best practices, along with offering technical support to both providers and patients (26), can mitigate technological barriers. Educating patients about the benefits and effective use of telehealth services through programs that demonstrate its convenience can build trust and increase utilization.

Developing favorable reimbursement policies that ensure parity in reimbursement rates between in-person and telehealth services can incentivize healthcare providers to adopt telehealth (27). Collaboration between healthcare providers, policymakers, and community organizations can create a supportive ecosystem, facilitating the sharing of resources and best practices (28). Continuous monitoring and evaluation of telehealth services can identify areas for improvement, ensuring they meet the evolving needs of patients and providers (29). Data-driven insights can inform policy adjustments and resource allocation, helping ND build a strong telehealth foundation, provide ongoing support, and engage patients and providers effectively.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is the use of Medicaid telehealth claims data, providing a comprehensive view of telehealth service utilization across two states with distinct demographics and healthcare infrastructures. The quasi-experimental design, utilizing SRA, enabled us to assess changes over time and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth usage.

However, there are limitations to consider. Reliance on claims data may not capture all aspects of telehealth utilization, such as patient satisfaction or quality of care. The lack of detailed patient characteristics limits our understanding of the underlying factors and social determinants influencing telehealth utilization. Additionally, the focus on Medicaid beneficiaries may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Unmeasured confounding factors, such as differences in state policies or healthcare provider practices, could also influence the results. Moreover, the large disparity in the number of telehealth claims between ND and MN presents a significant limitation. MN substantially larger dataset could lead to skewed statistical analysis, where trends in MN might be overrepresented, and those in ND might be underrepresented. The smaller dataset from ND may also reduce the robustness of the findings, as smaller samples are more susceptible to variability and may be less reliable in detecting significant patterns. To address these concerns, we employed SRA to adjust for underlying trends over time and conducted sensitivity analyses to ensure the consistency of the observed trends. However, caution is advised when interpreting these results, particularly in terms of these generalizability to broader populations or other regions.

Conclusions

Our study highlights significant increases in telehealth usage for SUDs and MHC during the COVID-19 pandemic, with MN experiencing a more pronounced initial increase followed by a decline, while ND showed a more sustained, gradual increase and decrease. These differences underscore the need for targeted strategies to enhance telehealth services, particularly in rural and underserved areas.

Policymakers should invest in broadband infrastructure, develop favorable reimbursement policies, support continuous training programs, promote collaboration between stakeholders, and implement monitoring systems for continuous evaluation. Healthcare providers should offer technical support, educate patients on telehealth benefits, engage diverse populations, and assess the suitability of telehealth for different patient groups.

Future research should focus on including detailed patient characteristics, assessing quality of care and patient satisfaction, investigating long-term sustainability, conducting cost-effectiveness analyses, and examining the impact of telehealth on health outcomes. Addressing these areas will strengthen telehealth services, ensuring they are effective, accessible, and sustainable in the long term.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for their invaluable contribution in providing access to data on telehealth behavioral services for the Medicaid and CHIP population.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-24-43/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-24-43/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Health Resources & Services Administration [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 21]. What is Telehealth? Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/telehealth/what-is-telehealth

- AlRasheed R, Woodard GS, Nguyen J, et al. Transitioning to Telehealth for COVID-19 and Beyond: Perspectives of Community Mental Health Clinicians. J Behav Health Serv Res 2022;49:524-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McBain RK, Schuler MS, Qureshi N, et al. Expansion of Telehealth Availability for Mental Health Care After State-Level Policy Changes From 2019 to 2022. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2318045. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dai Z. Telehealth in long-term care facilities during the Covid-19 pandemic - Lessons learned from patients, physicians, nurses and healthcare workers. BMC Digit Health 2023;1:2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nanda M, Sharma R. A Review of Patient Satisfaction and Experience with Telemedicine: A Virtual Solution During and Beyond COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed J E Health 2021;27:1325-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drerup B, Espenschied J, Wiedemer J, et al. Reduced No-Show Rates and Sustained Patient Satisfaction of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed J E Health 2021;27:1409-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snoswell CL, Smith AC, Page M, et al. Quantifying the Societal Benefits From Telehealth: Productivity and Reduced Travel. Value Health Reg Issues 2022;28:61-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gordon HS, Solanki P, Bokhour BG, et al. “I’m Not Feeling Like I’m Part of the Conversation” Patients’ Perspectives on Communicating in Clinical Video Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1751-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah DA, Sall D, Peng W, et al. Exploring the role of telehealth in providing equitable healthcare to the vulnerable patient population during COVID-19. J Telemed Telecare 2024;30:1047-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powell RE, Henstenburg JM, Cooper G, et al. Patient Perceptions of Telehealth Primary Care Video Visits. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:225-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, et al. Patients’ Satisfaction with and Preference for Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:269-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shigekawa E, Fix M, Corbett G, et al. The Current State Of Telehealth Evidence: A Rapid Review. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1975-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lucas JW, Wang X. Declines in Telemedicine Use Among Adults: United States, 2021 and 2022. Natl Health Stat Report 2024;1-11. [PubMed]

- Lee EC, Grigorescu V, Enogieru I, et al. ASPE. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 9]. Updated National Survey Trends in Telehealth Utilization and Modality (2021-2022). Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/updated-hps-telehealth-analysis-2021-2022

- US Census Bureau. Census.gov. [cited 2024 Jul 9]. Urban and Rural. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural.html

- Data Highlight - North Dakota Compass [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Available online: https://www.ndcompass.org/trends/Data-Highlight/Data-Highlight.php

- Older adults | MN Compass [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Available online: https://www.mncompass.org/older-adults

- Data Documentation | ResDAC [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 9]. Available online: https://resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf-30-cc/data-documentation

- Cottrell M, Burns CL, Jones A, et al. Sustaining allied health telehealth services beyond the rapid response to COVID-19: Learning from patient and staff experiences at a large quaternary hospital. J Telemed Telecare 2021;27:615-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- America’s Health Rankings [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Explore Population - Age 65+ in the United States | AHR. Available online: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/pct_65plus

- Thomas EE, Taylor ML, Ward EC, et al. Beyond forced telehealth adoption: A framework to sustain telehealth among allied health services. J Telemed Telecare 2024;30:559-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blandford A, Wesson J, Amalberti R, et al. Opportunities and challenges for telehealth within, and beyond, a pandemic. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1364-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haddad TC, Blegen RN, Prigge JE, et al. A Scalable Framework for Telehealth: The Mayo Clinic Center for Connected Care Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed Rep 2021;2:78-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Madigan S, Racine N, Cooke JE, et al. COVID-19 and telemental health: Benefits, challenges, and future directions. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne 2021;62:5-11. [Crossref]

- Doarn CR. Advancing Telehealth to Improve Access to Health in Rural America. In: Latifi R, Doarn CR, Merrell RC, editors. Telemedicine, Telehealth and Telepresence: Principles, Strategies, Applications, and New Directions [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021:157-67.

- Wootton AR, McCuistian C, Legnitto Packard DA, et al. Overcoming Technological Challenges: Lessons Learned from a Telehealth Counseling Study. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:1278-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee H, Singh GK. The Impact of Telemedicine Parity Requirements on Telehealth Utilization in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Public Health Manag Pract 2023;29:E147-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallegos-Rejas VM, Thomas EE, Kelly JT, et al. A multi-stakeholder approach is needed to reduce the digital divide and encourage equitable access to telehealth. J Telemed Telecare 2023;29:73-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khairat S, Pillai M, Edson B, et al. Evaluating the Telehealth Experience of Patients With COVID-19 Symptoms: Recommendations on Best Practices. J Patient Exp 2020;7:665-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Bhagavathula AS, Lopez-Soto D. Telehealth adoption for substance use and mental health disorders in Minnesota and North Dakota: a quasi-experimental study. mHealth 2024;10:31.